Dear reader,

Please note that the content shared here on Substack will differ from what appears in the printed book. While many of the themes, stories, and inquiries may echo across both formats, the book itself has undergone a thorough process of review, editing, refinement, and expansion. In that sense, the printed version holds a more curated, deepened, and embodied iteration of the work.

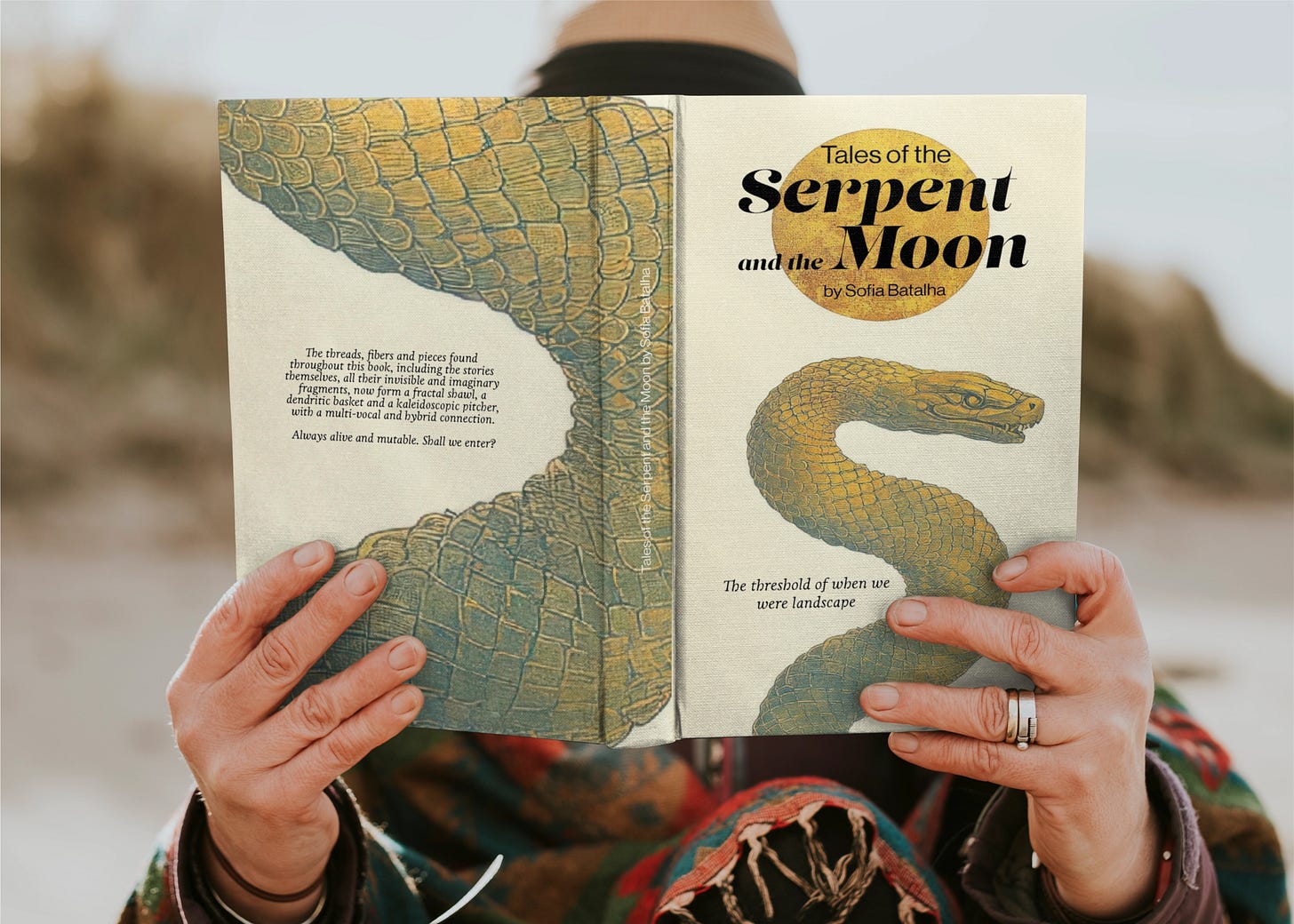

Think of the Substack as a living ground, where ideas are still fermenting, evolving, and growing their tendrils. The book, meanwhile, is a vessel, harvested with care, ripened in its season, and offered as a more coherent ceremonial bundle.

With tenderness for the ongoingness of becoming,

—Sofia

The Ancestry of Tales

Washer Mouras, by washing and wringing the target fabric of the tales' various cultural and historical layers, allows us to reach the conclusion that Portuguese researcher Sara Graça da Silva of the New University of Lisbon reached in 2016, where, together with Jamie Tehrani, an anthropologist at Durham University in England, they studied 275 stories from a database of over two thousand categories of folktales. This team of researchers treated stories as genetic information, passed on from generation to generation. “We don’t invent culture anew with each generation”, Tehrani says. “We inherit a great part of our culture.” Through their study they came to the conclusion that instead of the stories dating back to the 15th century, the researchers say some of these classic stories are between four and six thousand years old. As they excavated and retrieved threads from this ancient weaving, they found evidence that some tales were based on other stories.

More than a quarter of the stories were revealed to have very ancient roots —“Jack and the Beanstalk” was traced back to the split between Western and Eastern Indo-European languages more than five thousand years ago, and a tale called 'The Blacksmith and the Devil' appears to be more than six thousand years old. The team also found that the first versions of “Rumpelstiltskin” (then called “The Name of the Supernatural Helper”) and "Beauty and the Beast" first appeared with the emergence of the modern subfamilies of the Indo-European language, suggesting that these tales originated between three and four thousand years ago respectively. Tehrani says: "We find it quite remarkable that these stories have survived without being written down.” They have been told since before English, French or Portuguese even existed. They were probably told in an extinct Indo-European language. Sara Graça da Silva believes that the stories endure thanks to the “power of storytelling and magic since time immemorial.”

As researcher Claude Lecouteux also states, the central core of legends and traditional tales comes from a deeper spirit and essence than all the superficial fantasies attributed to them today. The ancient rituals and initiation ceremonies, including metamorphosis into animals, so present in traditional tales, are the expression of the deep human need to experience dangerous situations by facing exceptional experiences and opening the way to other dimensions and sacred realities.

It's possible to experience all this at the imagination level by listening to "fairy tales" or by dreaming and becoming the story's protagonist. These magical and mysterious experiences are similar to those of shamanic rituals traceable back to prehistoric times and preserved in ancient orality. Fairy tales as myths respond to archetypal truths, and the study of mythical geography, legends, myths and beliefs linked to places, reveals the importance of the local landscape in shaping tales and rituals.

I venture to underline the powerful web that contextualises us to places, serving as an anchor of old memories, that whispers to us in dreams and wakes up the memory of bones, from which all these living tales are recreated at every moment.

Wild Places and Guardian Spirits

Entering mythical geography, interweaving cosmic-chthonic cartography, whether in legends, myths or beliefs associated with places and landscapes, reveals the importance of the local landscape in the origin of tales, cosmologies and rituals. Here gods, goddesses and the various entities have been linked to particular and specific places since time immemorial.

Primitive animism, which (not only) anthropomorphises natural forces, is a form of perception that allows engagement and dialogue with extremely archaic creatures, animals, and even the "inanimate" forms of stones and rivers, for the sacred continually escapes from forms that define it. Despite this natural fluidity of form, these spirits are often imagined as humans (there are several kinds of humans, so this is not an anthropomorphic-centered consciousness) so that not only feelings but also personalities are attributed to them.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cosmic-Chthonic Cartographies to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.