Through this communal journey, we will reclaim the immanent grounding force, and geomorphic seasonal bodies of these diverse primal beings, for we are opening ancient routes toward myth, place, and ecology. Our horizon in this pilgrimage is not above, but below, for we will find them in the underworld, the ancestor's place; it is not anthropocentric or anthropomorphic, but more-than-human, geological, and ever-shape-shifting. This is a journey to remember these chimerical beings as eco-mythological living forces.

May we be fierce enough to open these ancient, rugged pathways through thorny bushes and giant boulders. May we be gentle enough to devote our heart-centered ecstatic fascination and visceral accountability toward their old body and healer devotees.

My proposition is simple, so simple it has been bypassed for 1500 years, becoming “just” scenery, an inert and silent backdrop for human action, like an inferior child-like lens. The path of re-remembrance of this essay is to knit and knot, unfolding Our Lady of Orada as hybrid and ancient chthonic beings who are the living landscape themselves. Remnants of animistic eco-mythological local cults to the Mountains and Waters, through fertility, birth, and death rites.

To consider this rhizomatic speculative hypothesis, we must explore etymology, along with the folktales and oral stories of some of the local Portuguese Orada chapels. For this to happen, we need to consider the inevitable seasonal, biological, and psychic entanglement of the human body to the place it inhabits, to the landscape “it is.” Together in emergent poly-symbiosis.

We start this perilous journey, with a chaotic and entangled yarn, aided by two threads in our handloom. The first one is that the pervasive Portuguese Marian Christian Sanctuaries (dedicated to the Virgin Mary in her many local forms and names), hold, in deeper layers, memories of these animistic beings. I wrote about this in my book, The Sanctuary: “These mystical cults and native primal goddesses were translated into the Christian language, submerged in the so-called cult of Mary, "The Holy Lady." In Portugal, these archaic seasonal eco-mythological goddesses were labeled in the overarching term "The Lady," in cyclical iterations of local Christian festivities and shrines, which appropriated earlier pagan sacred times and ancient rock sanctuaries.” The second thread in our handloom concerns the Moorish women, Enchanted Serpent Women, to whom I dedicated an entire book, Tales of the Serpent and the Moon, and also discuss them in the following book, The Sanctuary: “(...) these beings are not just Muslim Water genies or enchanted Moorish princesses, being much older, they are ophidic fairies from the underworld, who always live by the Water, the guardians of the ancient chthonic mysteries of Death.”

Now, before we take the first step, let's take a deep breath and pour some water onto the ground and sprinkle it around our bodies.

A loom always starts with the first thread

This research-prayer led me to find twelve active Lady of Orada sanctuaries throughout the country, and this is not a thorough quest, for there might be others, in ruins, lost, forgotten, or just not listed (like the Our Lady of Orada hermitage in Évora, renamed in 1361 under a different patron saint). The ones I’ve found range from churches to chapels, hermitages to convents, built between the 12th and the 17th centuries, from north to south. Most of these places still have ongoing seasonal celebrations around the summer solstice, ranging from early May to mid-August. The official devotion and built chapels for Our Lady of Orada are deeply intertwined with Christian Portuguese conquest and history, connected to battles to expand or protect the Portuguese borders, from the invading forces coming from the neighboring Castela kingdom and northern African Muslim settlers. But, before all the wars, slaughters, battles, and domination, she was already here, and the granite masonry church structures were just a way to domesticate and mark the land toward the new Christian law —a recent translation.

Local folk stories still carry echoes of primeval rituals, and we can find a very rich imagery, connected to some of these Orada temples, that will help to bring this Lady back to Life, back to rock, water, and land.

Like the story of the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Orada in Vieira do Minho, up north, where, in the 15th century, after the image of Our Lady disappeared from the church altar for three days, a beautiful and polite lady appeared in the parish. Meanwhile, a plague attacked the local population, and this woman claimed to know how to treat the disease. She went to the homes of the sick, made tea from a plant she had in her saddlebag, and then, adding other herbs, prepared a bath. She recommended that people wash themselves with St. Mary's herbs and elderberry leaves, that they smoke their houses with rosemary, and that they wash their clothes often. This mysterious Lady never stopped attending to the sick, from dawn to dusk, never accepting food or invitations to stay. After forty days, the plague subsided, and few people survived the scourge, but in this particular village, no one died. The helper Lady disappeared just as she had appeared, and everyone wondered about her mysterious identity. Then someone remembered that her clothes and her face were the same as those of the Lady of Orada on the church altar. A spring emerged after the miracle, and the locals started the tradition of a seasonal pilgrimage to her shrine, thanking her for all the help and protection.

The oldest Lady of Orada chapel, in Melgaço, documented since 1166, has a stone cross from 1567, thanks to Melgaço having been spared during a period of the plague. There is also an ancient tradition that, many captives who were in Moorish lands were freed and appeared at the doors of this temple, with the shackles and chains with which they were bound. A book, published about 300 years ago, tells about the ongoing miracles and pilgrimages of this place. Like the yearly pilgrimage by the mothers, from May to early June, to make offerings. Or, in times of need of sun or rain, many locals sing and ask for gentle weather.

The tale of Our Lady of Orada, in Castelo Branco, brings even animistic threads. It is said that a village maiden, was stricken with a terrible illness that made her belly swell very much. Her father, took her to a wild and dangerous place, full of thorny bushes and many ferocious animals, so that his sinful daughter would be devoured. In other versions, it is the young woman in despair over an unwanted maternity, who encounters an old ascetic, who withdrew from the community to devote all his days to prayer and penance in the wild woods. Eventually, the Virgin appeared in this wild place and told the maiden that the swelling in her belly was a snake that had spawned in her, advising the girl to place herself upside down with her head over a dish of warm milk. The girl did so, and the snake, attracted by the milk smell, came out of her mouth. The father, repentant, had a chapel built on the apparition site, where a miraculous spring had started to flow, and a snakeskin was placed in the shrine.

In the Our Lady of Orada temple in Odemira, one legend goes that a pilgrim stopped at Orada to recover from illness and, as a token of gratitude, carved a wooden statue from one of the Ash trees alongside the creek. Later, this statue was seen simultaneously at Orada and São Teotónio parish. Another tale, explains how the statue was stolen from the temple, but the horses refused to leave the property and the robbers fled on foot.

Down south in Albufeira, at the Hermitage and later Convent of Our Lady of Orada, the tradition brings together hundreds of people, known for blessing the village's fishermen. The story goes that the inhabitants of Albufeira, once a fishing village, saw several miracles of Our Lady, witnessed in the "ex-votos" that are kept in the Orada Hermitage. It is a religious event of great significance for the people of Albufeira, which has been held for over 500 years. During the seasonal celebrations, the statue is taken from the altar and goes by the sea to bless the fishermen's boats, ensuring a bountiful fishing year.

Encountering the territory through devotion

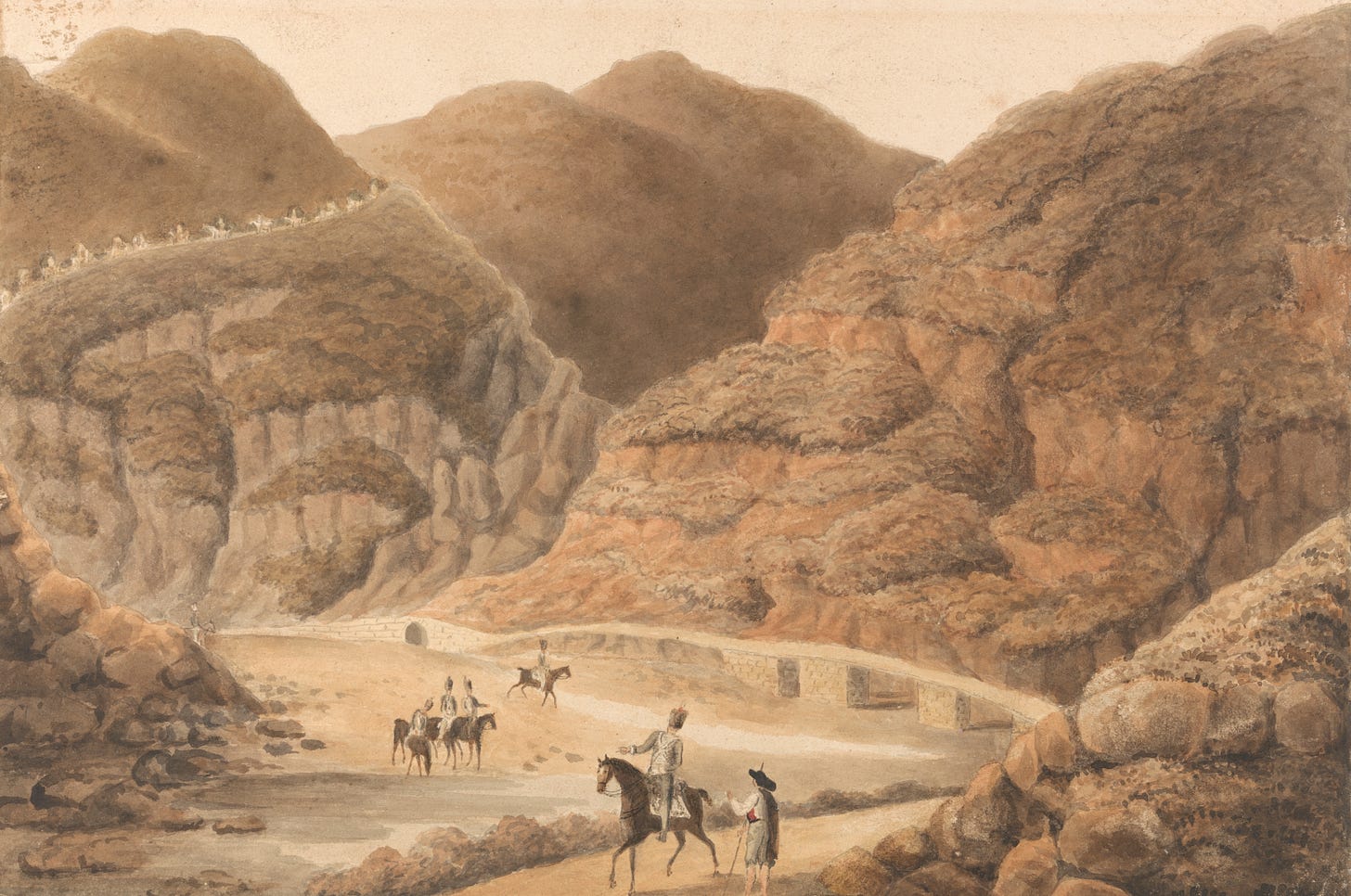

There are indelible matrixes in the yarns of these tales, echoes of contextual pagan myths and wisdom. The first matrix concerns the common landscape holding the miracles and apparitions of Our Lady of Orada. Most of these sanctuaries were built in high and secluded, demi-wild places, with water flowing down the hills and surrounded by dense groves. More often than not, the ancient granite chapels are locally known to be hermitages, the word coming “from eremia "a solitude, an uninhabited region, a waste," from erēmos "uninhabited, empty, desolate, bereft," from PIE *erem- "to rest, be quiet.” The term waste, empty, and desolate, is applied for these are not agricultural lands, but unruly ones; but also contain the devotional silence of praising the sacred.

Our Lady of Orada is marked and celebrated on mountain tops, near fresh-water streams, fountains, or springs, usually surrounded by abundant lush woods and inspiring sceneries, remnants of the concept of Greek Temenos, or the consecrated Celtic woods.

These are sacred healing waters, and miraculous springs still heal pilgrims in collective ritual washing during summer solstice festivities. Local sayings recall the ritual ablution and washing of the eyes and head (Vieira do Minho), and both people and animals recover their full force while bathing and drinking in these waters, which have wider healing properties, for they could raise the bread if kneaded before sunrise (Odemira). May we now recall and hold the second thread in our handloom, concerning the so-called Moorish women, the demonized chthonic serpent guardians, inhabiting springs and thresholds. These ancient feral beings are usually seen by the waters, combing their shiny hair, on full moon nights and around the solstices, and they can curse or bless you.

Holding these shape-shifting serpent guardians close to our hearts, let's take a detour into the fractal roots of the word Orada. The first layers of the ancestry of this word connect it to the act of prayer, from Latin ōs, ōris, meaning mouth, from Proto-Indo-European *h₃éh₁os —recalling the serpent coming out of the maiden’s mouth, seeking warm milk. Indeed, the common meaning of Orada in local folktales holds devotional action, from the Latin ōrāre (coming from ōrō), meaning to speak, speak before a court or assembly, pray to, or plead. This holy act also means to express, communicate, beg, converse, discourse, or speak to a divine being. A deeper origin and history of the word Orada, tether it to the Proto-Indo-European *h₂er- (to pronounce a ritual), the Hittite 𒅈𒌋𒉿𒄿 (to worship, revere), 𒅈𒄿𒄿𒀀𒄿 (to consult an oracle), the Attic Greek ἀρά (prayer), and the Sanskrit आर्यन्ति (praise).

Oratorio, from the same root, also finds its way in this loom, pertaining to church in Latin, oratorium, a place of prayer, an oratory, or chapel. Oratorio also connects to musical compositions, in prayers and hymns.

There is also the thread coming from Latin aurum (English gold, Portuguese ouro), from Proto-Italic *auzom, and Proto-Indo-European *h₂é-h₂us-o- (glow) —recalling the water glitters and the shiny golden hair of the Serpent Women under the moonlight, and the hidden gold this being might endow you with. In Old English, there is the word ore, meaning unwrought metal/brass; possibly from ār (ore, brass, copper) and influenced by Proto-West Germanic *ōrikalk (copper ore, brass), borrowed from Latin orichalcum (copper ore, brass). Perhaps connected to the Low German Ur, Uurt, Uhr, Urt (compact, reddish, iron-bearing soil), and Early Modern Dutch oor, oore (mine; lead ore; vein bearing lead and silver).

Let's breathe for a while here, holding the threads that weave ancient patterns of the term Orada, connecting the pronunciation of rituals, the devotional consultation of oracles, sung worship and place prayers, to the sacred glow of gold and silver, the shimmer of waters, or the glimmer of copper and brass ores, coming from the mouth of the Mountain. Indeed, in the Iberian Peninsula, there is the ancient pre-roman tradition of throwing metal (silver, gold, iron, or copper) coins into thermal or sacred fountains, springs, or wells, as an offering to the local deities. Thus weaving together the devotional rites to sacred waters, and oracle rituals with the metal ore. The word Orada is starting to give away its secrets.

But let's go deeper.

From the entangled yarn of invocation and shining metals, let's pick up another thread, where “oro” comes from Ancient Greek ὄρος (óros), meaning Mountain or high ground, and ὄρνῡμῐ (órnūmi), also pointing to stir, to urge on, and incite. The Greek “oro,” thus concerns everything related to the mountainous environment, from tectonics to hills, mountain chains, cliffs, and ridges. Throughout the territory, Mountain geo-ecosystems are hugely diverse. Indeed, Mountains occupy about 1/4 of the Earth's land, harboring valuable biodiversity, and supplying fresh water to an estimated half of humanity, says the UN Environment Program.

The Ancient Greek ὄρος (óros) probably derivates from PIE *heros-, meaning elevation. Ὄρος, the Greek “oro,” might also connect to ὄρνυμι (órnumi), meaning “I raise” –the sacred journey of climbing the steep mountain path to connect to higher powers in devotional rituals.

Before our eyes, and under our feet, Orada is becoming the Moutain herself, the living place of worship and revelation. Our Lady of Orada is unfolding as an ancient more-than-human geo-ecological being, who bears miraculous water and metal talismans in her womb. From the depths of time, she is rising once again, becoming landscape.

But we can still dig deeper.

Orada is indeed a rich living wor(l)d, with evocative tendrils and still holding more mysteries. There is a thread relating to time in Portuguese, Catalan, Galician, and Occitan, from the Latin hōra, meaning hour or now. In Catalan, there is also the Latin root aura, meaning breeze or calm weather –recalling how in Melgaço there is a tradition of asking Our Lady of Orada for calm weather. In Azerbaijani, there is the locative ora, meaning there, that place. In Latin, ōra, also means shore, or edge hill. Possibly related to Hittite 𒅈𒄩, er-ḫa-aš /erḫaš/, implies a line, or a boundary; perhaps from Proto-Indo-European *h₁erh₂-, indicating border, rim, frontier, limit, edge, sea coast, region, or country; an extremity, brim, margin, end, boundary, or limit. Connecting to the Vulgar Latin *orulāre, from *orula, and French orle, define the borders of a district, sector, precinct, or parish. In Portuguese, we have the derived term “orla marítima,” speaking of the sea border. There is also the act of rimming, that is, forming a rim around something. It is important to note that the traditional seasonal solstice celebrations, regardless of Christianization, still entail a ritual circumference walk around the temple, sacred spring, or miraculous fountain, thus encircling and creating a ceremonial boundary. After climbing the mountain to the granite shrine, there are the traditional three to nine laps pilgrimages around the center, demarcating the edges of the devotional space and time, inviting the pilgrim, to ecstatic contemplation and prayer. Not forgetting the ritual riming of clothes and the ritual menstruation moon belts.

May we breathe deeply now, acknowledging that, since time immemorial, Mountains are space and time mythical beings, marking boundaries on the territory and defining time cycles, standing as open-air sanctuaries for ritual drinking and washing, thus encountering the sacred.

May we recall Our Lady of Orada, the edge rimmer, intertwined with Christian conquest and the expansion or protection of the Portuguese borders; but also in a deeper mythic thread, with the Serpent Women, the guardians of liminal spaces between death and re-birth, along with the embodied thresholds of being born, delivery and dying. Our Lady of Orada, the geo-polymorphic being, the mountain body who holds sacred time, in seasonal changes of weather, light, and temperature patterns, the one who defines the consecrated place, ensuring bountiful water, crops, and life.