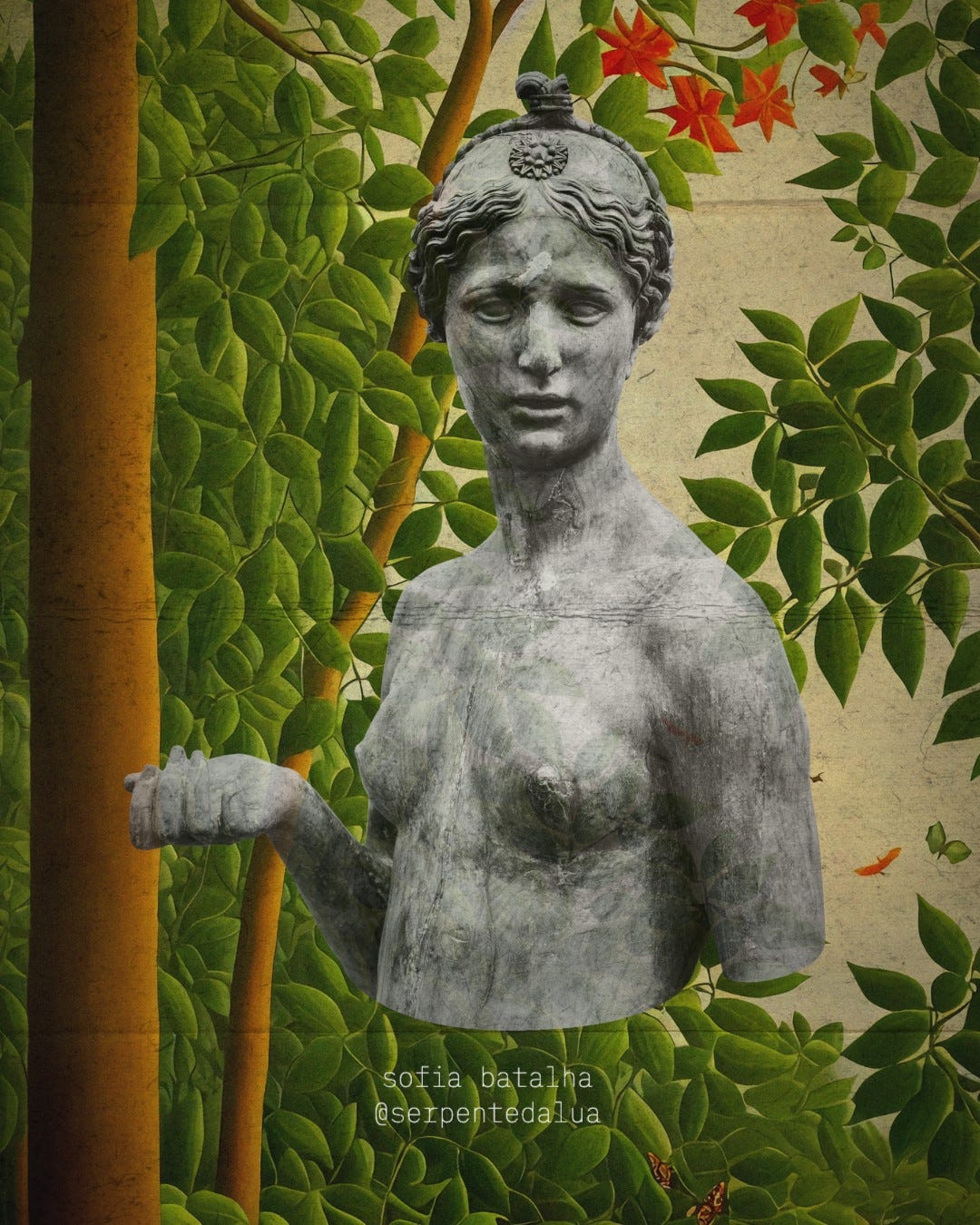

What if we ventured to look at tales as maps beyond human psychology?

Research-prayer with Eco-Mythology

What if tales were treasure chests of metamorphosis and deep connection?

What if, in the fabric of their actions, territories and characters, we found ancient songs of other-than-human relationships? Those that enrich us and tell us that to be human, we can never be without animals, plants, the ground, the stars or the elements. We’ve have never been alone.

This has been my research-prayer proposal with Eco-Mythology.

Re-imagining stories as ecological cartographies of metamorphosis opens the possibility of looking at ourselves in an integral and profoundly participatory way. The threads of the stories at the bottom of this treasure chest weave on the primal wisdom of the fruitful patterns of the seasons: sowing, reaping, hunting, weaving, dying, and regenerating. They record the cyclical movements of human communities integrated into the landscape in symbols and metaphors.

In fact, with their origins more than 7,000 years ago, many tales (fairy, marvelous, folk) that we think of today as being for children {1} are maps of complex, intergenerational collective wisdom. Maps of relationships and ecological patterns, from the stars and seasons to migrations and fruit ripening, retaining the wisdom of living in a particular place. Tales are entire cosmologies. They also record ancient memories of catastrophic events. Through the human gaze integrated into a familiar landscape, where all species and elements are relatives, the rhythms of multiple intertwined cycles are codified in myths and rites. Whispered, sung, and told in sacred protocols and practical decisions, with knowledge of place and season connective tissues.

As a brief example, I'll give you an essential story from the south of France, taken from the book Metamorphosis - The Dynamics of Symbolism in European Folk Tales by Francisco Vaz Silva. The tale goes like this: "There was a seamstress who lived in the upper part of the village with her sister. When I met her, she was very old. She used to go to bed on All Saints' Day until the swallows returned."

This simple tale tells of the rhythm of the old seamstress who sleeps all winter in the upper part of the village. The old woman has a witchy tone. And the fact that she is a seamstress is also quite symbolic and archaic, along the lines of metamorphosis and skin changes.

The seamstress and the association with a winter disappearance are by no means coincidental. The author links the old seamstress' annual retreat to bed at the beginning of November with the appearance of the Pleiades. The Pleiades consistently mark the transition between contrasting seasons in Europe and many other parts of the world. The awakening of the old woman is related to the swallow that begins to sing in February, the ancient first day of summer, when bears and snakes end their hibernation. We then have an old seamstress, who goes through a similar hibernation to the snake and reappears during seasonal renewal. The old seamstress personifies the fairy serpent and the cycles of reemergence, following the cycle of rebirth of the seasons. She has an apprentice seamstress, her younger sister, who follows the same maturation cycle. This short story contains deep layers of the menstrual and ecological time rhythm, changing skins, fertility, and death. The two characters are ecological archetypes of ritual and initiation, containing profound ecological wisdom.

Despite the richness of interacting with the tales solely from a psychological perspective, we must be aware of the limitations of Western anthropocentric and hyper-individualistic psychology, which limit these stories' complexity, biodiversity, and ecological wisdom.

This contemporary fragmented gaze reduces the nature and intricacy of the tales, making ancient relationships invisible. When we lift the lid on the treasure chest, what we find inside is much more than the recent anthropocentric psyche. We discover a deeply relational and ecological consciousness, where humans can be animals and animals speak, where forests, rivers, and mountains are places of access to the other world. Where enchantment is the mystery of the more-than-human. Where wisdom is animistic and integrated.

-

{1} it's essential to note what “being for children” really means in this cultural context. Something that is for children is also often labeled as ‘uninteresting,’ ‘too simple’ or even ‘irrelevant’ because it is naturally hierarchically inferior. Let's now think about how these extra labels provide information about how we label childhood.