Dear reader,

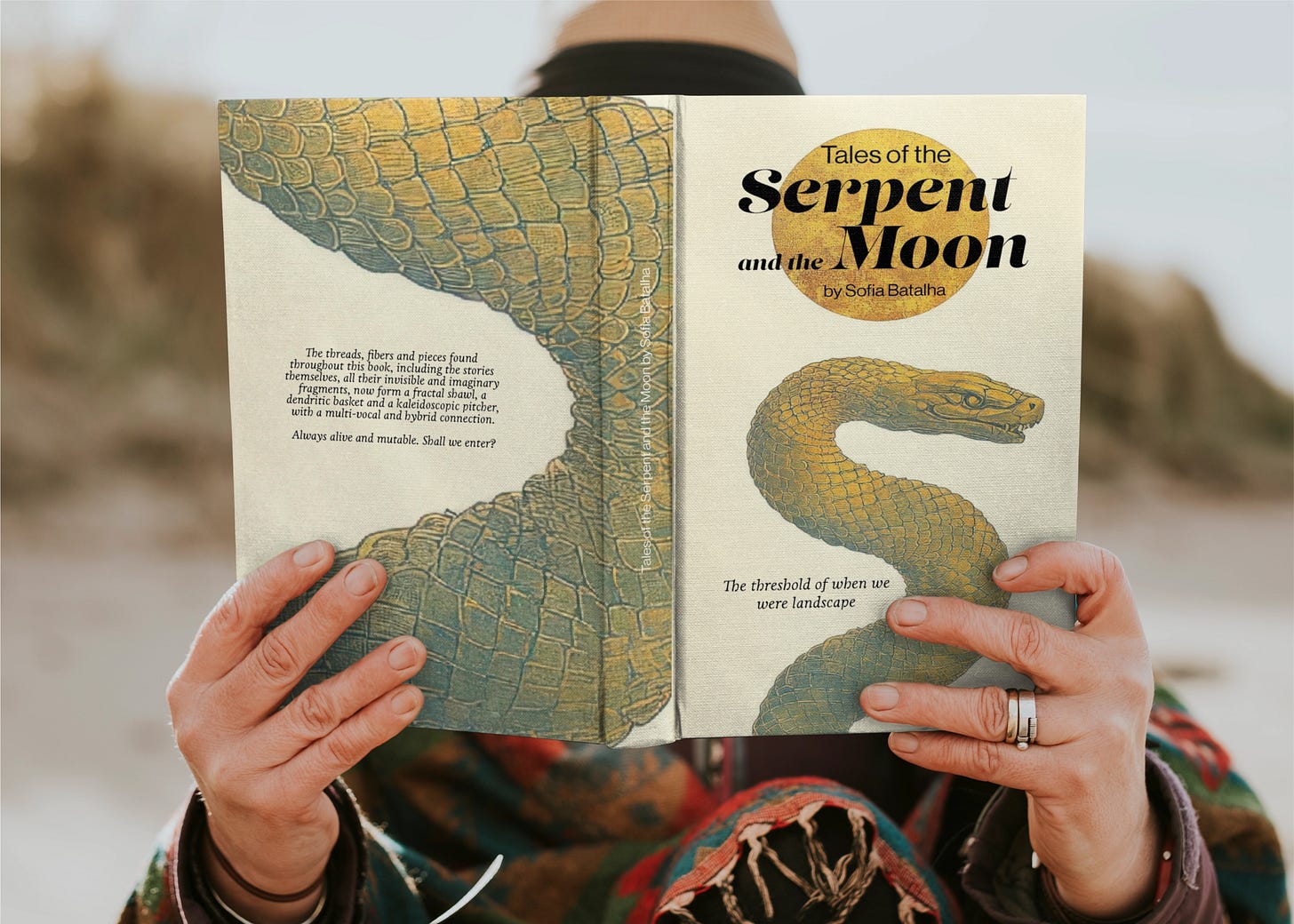

Please note that the content shared here on Substack will differ from what appears in the printed book. While many of the themes, stories, and inquiries may echo across both formats, the book itself has undergone a thorough process of review, editing, refinement, and expansion. In that sense, the printed version holds a more curated, deepened, and embodied iteration of the work.

Think of the Substack as a living ground, where ideas are still fermenting, evolving, and growing their tendrils. The book, meanwhile, is a vessel, harvested with care, ripened in its season, and offered as a more coherent ceremonial bundle.

With tenderness for the ongoingness of becoming,

—Sofia

What breathes through Brufe’s tale

What follows is not a symbolic interpretation of the tale, exiling it in a single narrative. There is a unique symbiotic dialogue with the tale’s living layers that is yours to feel, sense, and travel through. The following words are mythical, historical, and place transcontextual information that resonate with the tale’s pulsing realm.

When I started unraveling this tale, I intended to base it on Sleeping Beauty. Despite all the creative diversions, it shared some aspects, notably Brufe's ecstatic, incubating sleep in the dolmen, equivalent to bears' hibernation and the enchanted maiden's sleep. This tale was woven around an intense and vivid dream —I’ve found myself inside the Monster Sanctuary, feeling its potent breathing and entanglement, as described in Brufe's experience inside the Dolmen.

I was also, at the same time, wandering through the relics of Portuguese toponymy that records the old and abundant presence of bears in this peninsular territory, with the last brown bear that lived in Portugal being killed in 1843 in the Gerês area, as told in the book “Urso Pardo em Portugal - Crónica de uma extinção” (title in English: The Brown Bear in Portugal - Chronicle of an Extinction), by Paulo Caetano and Miguel Brandão Pimenta. Centuries earlier, these animals were found throughout the country. This great woodland predator was distributed from North to South in the country and was exiled to its last stronghold in the mountains of Gerês.

Serra D'Ossa

So, everything came together in the tale of Brufe, whose name in Portuguese and Galician is the feminine variant of Berwulf, which means bear (ber) and wolf (wulf).1

Many cities, localities, and territories in Portugal have derivations of the word bear in their name, such as Ossa or Murça. Probably, their foundation was related to ritual, shamanic, ecstatic, or animistic connections between this sacred animal, the local populations, and the territory.

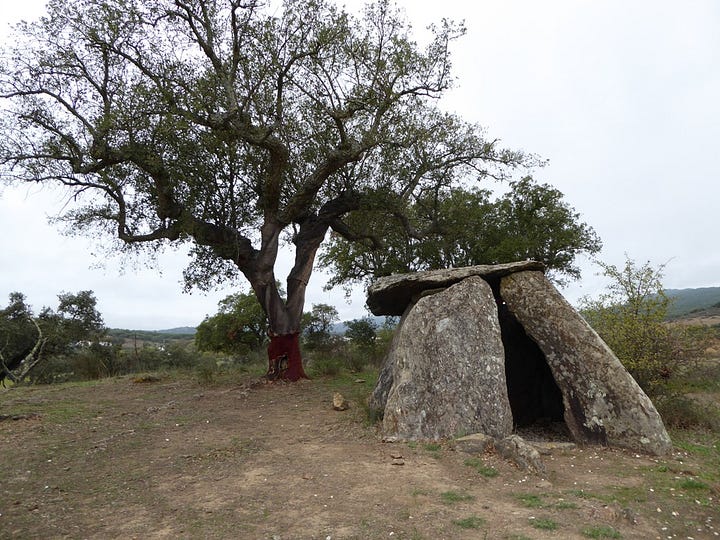

Thus, related to the nomenclature that reveals the ancient presence of bears in the territory, such as the ancient stone rings built to protect the hives from the attacks of these animals, we have the place where the tale unfolds: the geological accident in the middle of the Alentejo plain, the Serra D'Ossa (in English: Ossa mountains, with Ossa meaning “bear”), in the municipality of Redondo, in the District of Évora. This is a place shrouded in traditions, rituals and mysteries. Inhabited since the Bronze Age and a place of devotion to shepherds, it was home to the first hermits of the Christian Era who supposedly made it magical, molded it, and gave it its name. Even today, we still have the cork oaks, holm oaks, pines, and arbutus trees as a legacy of this ancient caretaking. It so happens that over a thousand years ago, when the first hermit monks arrived, the mountain had already long been inhabited by primitive beliefs that saw it as a sovereign and sacred place, which the many dolmens on its slopes reveal.

It is believed that the hermit monks shaped the region, first in caves and later in convents. In Brufe's tale, these hermit monks were fabled as the ancestral female guardians of the place, genii loci, animal, and wild, linking and transforming the bear toponymy to the legacy of the Christian monks.

Also, according to local custom, there were many flocks of sheep on the top of Serra D'Ossa and, on the winter solstices, the shepherds would climb to the highest point to bless their animals, bringing offerings of a pair of horns and a bag with food for Saint Cornelho (a name related to horns), a theme I used for Brufe's offerings to the Sanctuary.

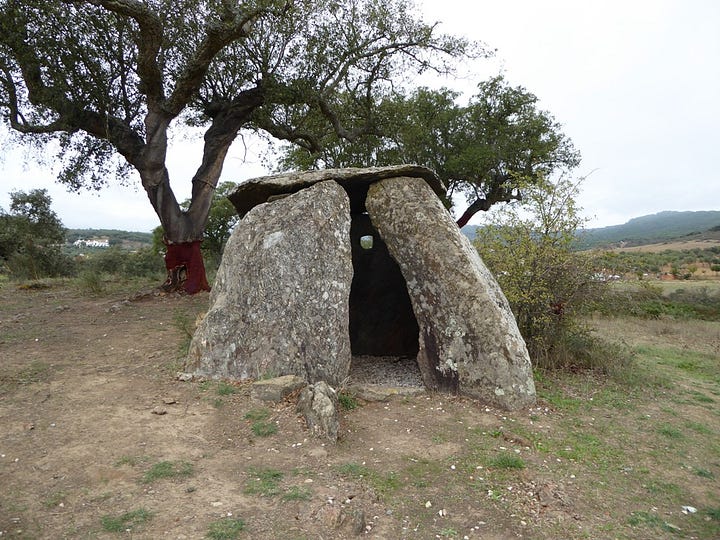

Candieira Dolmen and Sacred Hibernation

The Monster Sanctuary was imagined as being anchored in the dolmen of the Candieira estate, a funerary monument from the Neolithic period, between the 4th and 3rd millennium B.C. This dolmen has a mysterious hole in the top, called the "Soul Hole" by the local people.

Because of verbal similarities to the place name, Candieira, I refer here to Candlemas Day, which occurs six weeks after the winter solstice and relates, in the Northern Hemisphere, to the end of the bears' six-week hibernation (sleep as incubation, fermentation, decomposition, and sacred transformation). The bear's apparent conquest over death in its annual hibernation makes it an excellent mediator with the other world. In some places in Europe, in primeval times, a maiden was left in the forest as the bear's bride in a bear-human marriage-gift-sacrifice ritual when the animal emerges from its hibernation.

The Bear

The sacredness of the bear can be traced back to the Neanderthal man in ritual caves in the Alps, dating back to at least the 100th millennium BC, and there is a constancy of bear rituals from the Upper Paleolithic to the present day. Some ancient cultures refer to the bear as the master of the forest or the wise one, and because of their great strength and fearsome appearance, bear mothers are often called "giants" or "ogres" in legends.

This ancient echo of the bear as a sacred animal finds traces throughout archaic European mythology:

Merope, the name of one of the Pleiades stars and the daughter of Atlas and Pleione in Greek mythology, may be a bear, having the same substance, nature, or essence, as honey;

Callisto, the bear sister of Odysseus, was catasterised — the mythological act of turning a character into a constellation to eternalize it in the sky — into the bear constellation, Ursa Major, being one of the two bear constellations, mother and daughter, that revolve around the polar star;

Zeus, the great god of Olympus, was fed honey by bears in a cave during his childhood;

The bear goddess, Artemis, whose name is derived from artkos (bear in Greek), and whose young priestesses were called "bear cubs."

We also have the foundation of Madrid: the city's emblem is a strawberry or arbutus tree, with a bear tearing off the bark or picking red berries, which is also a way of releasing the lifeblood of the host trunk for magical fungi, making the tree's connection as the axis mundi, and the archetypal tree of life in an animistic and shamanic view.

Bears and menstruation

Part of the bear's archaic sacredness also relates to the folk wisdom that menstruating women must beware that they will attract bears. The pig or the boar is similar in its response to the female human pheromone, hence the bear's special significance in the bear cult's maidens sacred to Artemis, and the pig in the myth of the boar hunt, ancient male and female initiation rituals. This primal connection recalls the doubt in Porca de Murça, whether it is a sow, a she-bear, or both. I would recall that hunting is a biological necessity and a ritual —the hunter asks permission from the animal's spirit to hunt it.

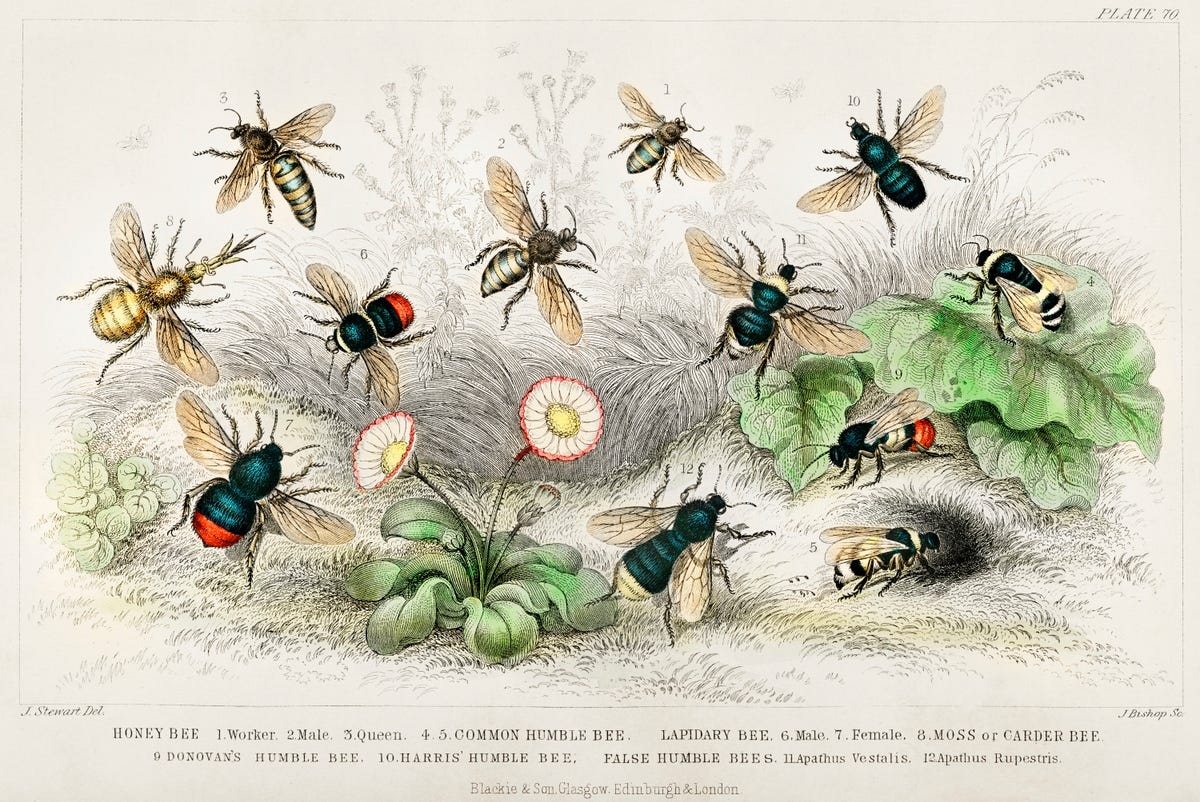

Shamans, Bees, and Honey

To survive hibernation and with winter approaching, the bear, omnivorous, voraciously eats all kinds of berries and other fruits. Its relationship with bees is special, since the high nutritional content of honey makes it an essential food for the animal to fortify itself before the winter sleep. On the other hand, the bear's thick layer of fur makes it highly resistant to bee stings. Honey may appear to cause its lengthy disappearance, reinforced by the involvement in the whole myth of the bee sting, which can also be psychoactive, derived from nectar harvested from magical flowers. The potent image of symbolic immortality relates to the long immortal sleep of the hibernating, bee-eating bear.

There is indeed a primal and very ancient relationship in European shamanism between bears and bees, for shamans are depicted with swarming heads of bees or as shaman-bees, and bear skins are worn in transmutation rituals.

Preparing for winter hibernation, the bear does not hesitate to eat fungi, amanita muscaria mushrooms, deliberately seeking the ecstatic experience. The "intoxicated" bear is easy prey during the six weeks or so of its hibernation, and hunters possibly shared caves with these animals. The plants and honey that induce the bear's sleep cause shamans to connect with the sleeping animal's powers.

In the tale of Sleeping Beauty, as told by the Brothers Grimm, the bee, with its buzzing sound, is instrumental in awakening the sleeping maiden, which I drew upon for Brufe's tale, to bring her in and out of sleep in the Monster Sanctuary.

We move on to the vital duality of the bee's venomous sting and psychotropic or toxic honey. Bees are shamans, and the flowers whose pollen they collect, being psychoactive, create intoxicating honey. The word "bee" itself is of great antiquity in Indo-European, derived from the Latin apis and giving rise to the word abelha in Portuguese. "Bai" in Sanskrit, and “bee” in English, mean ‘bzzz’, the onomatopoeic sound of these insects' swift wings, and one of the oldest descriptors of the ecstatic experience of intoxication: the pulsating auditory sensation that marks the beginning of a visionary experience.

We maintain this space of connection of the metaphor between the shaman and the bee open by recalling the priestesses at Delphi, the Melissas, and Artemis, Demeter, or Cybele. The bee priestesses of Demeter were responsible for rituals in Eleusis in honor of bees, the goddesses themselves having taught these insects to build their honeycombs in the hollows of trees. At Knossos in Crete, bare-breasted bee maidens' sisterhood engages in a ritual dance amidst a meadow blooming with daffodils (a narcotic flower), which precipitates the spiritual abduction of perseverance.

And also with the honey collector depicted in a cave wall in Spain. The "Spider Caves" are a series of caves in Bicorp Municipality in Valencia, Spain. Early humans used these caves, and this painting, referred to as "The Man of Bicorp" is thought to have been painted by Epipaleolithic humans, around 8000 years ago. It was found among other paintings of important facets of life, such as hunting and ceremonial dancing, showing just how culturally significant bees were at the time.

As referred to in “The Hidden World: Survival of Pagan Shamanic Themes in European Fairytales”, both the word “poison” and the word “arrow” have the same origin in ancient Greek, just like the bee's dual role as a collector of the essence of flowers, from which it produces the exhilarating honey and injector of the toxins in its sting. This insect, by stinging, can alter vision. Snakes were also thought to derive their venom from the plants on which they feasted. The ecstatic dances of the shamans or the inspired compositions of the poets were metaphorically honeyed, derived from honey, and the poets are described as feeding like bees. In Plato's Symposium, the ancient Greek shaman Diotima, mentions that the intoxicating honey drink was older than wine.

Honey is also an ancestral symbol of new life achieved through initiation rituals. It is an antiseptic, used as a preservative, occasionally embalming corpses, keeping them intact until burial. In some ancient rituals, it was also poured as an offering to the dead.

Like the bear, Bees symbolize immortality, also relating to female leadership. The bee is a messenger or intermediary of the gods; they are souls and divine messengers. The swarm indicates the presence of divinity, just as the buzzing describes ecstatic communion with other dimensions. The honeycomb is a metaphor for sacramental food, which may speak of purification rituals.

Boars

Throughout these posts, I speak about Wolves and Serpents and their metaphorical antiquity in the tale of Ananta the She-Wolf Woman. However, there remains to be mentioned here, the Boars, those extraordinary animals, ferocious and wild, representatives par excellence of the powers of the underworld. You can also check about the Iberian shamanic cosmos on the Braganza Brooch.

The Boar is one of the animals that traditionally function as a psychopomp, a word originating in the Greek psychopompós, which joins psyche (Soul) and pompós (guide), and which designates an entity whose function is to guide or lead us between dimensions. Boar hunting is a classic puberty initiation ritual. As mentioned earlier, the Boar is one of the few animals, like the Bear, that responds to the human sexual pheromone, so it is one of the shamanic animals of primal female entities. It is often portrayed as the guardian of portals between worlds or dimensions.

From the Book - Contos da Serpente e da Lua, Sofia Batalha

For references and other tales, here

http://toponimialusitana.blogspot.com/2006/06/topnimos-terminados-em-ufe-e-ulfe.html

very interesting!