Šī-dūrī sābītu

As I mentioned earlier, in the most recent fragments of the Epic – some 1500 years removed from the original story – Siduri loses her divine character. Becoming a prosaic prostitute (here, according to the modern concept, also devoid of sacredness), devoted to the basic pleasures of Life. Gilgamesh aggressively approaches her in his inexorable quest for individual immortality. The tavern-keeper loses her name, her advice disappears, and her presence is reduced to a line. Her character and presence are belittled and demeaned as a hedonist, never comparable to the great hero's transcendent spiritual concerns.

After all, she is just a banal young tavern wench, with a brothel to satisfy male pleasures, which generates a mixture of shame and humiliation at her real ability to help a king and hero in his quest for the transcendent.

In fact, this debasement happens systematically throughout the various versions with all the sacred female characters, which makes this story a valuable document of the rise of dissociated patriarchy and addiction to transcendence and conquest.

As an example, we also have the priestess of Inanna-Ishtar, Shamhat, whose presence has been reduced to "prostitute" or "sacred girl of the temple." In fact, she is a hierodule, which means "servant of the goddess," occupying a vital position in the temple. Her functions, linked to the cult of Inanna, would include ecstatic sexual rites (sacred prostitution is difficult for modernity to grasp, as there is no awareness of its ceremonial complexity, which would involve lengthy ceremonies devoted to beauty, tenderness, sensuality, and consensus). Moreover, in Inanna’s temples, hierodules were both sacred virgins and blessed prostitutes. The demeaning of the feminine and Nature can also be found in Gilgamesh's refusal and offence against the very deity of fertility, Inanna-Ishtar, which I won't go into here.

The eco-mythological keys to Siduri are many, primal and profound. I'm not going to explore them in academic terms (in transcriptions of comparative, linguistic, historical or ethnographic studies). I'm interested in where it brought me and how she presented herself in our shared dreams. Furthermore, I intend to convey the sensations Siduri imprinted and anchored in me: the cathartic entanglement with the nourishing decomposition of fragments, pains, sorrows, passions, and joys in the fertile soil of her garden of paradise.

So, if Gilgamesh represents the arrogant and self-centred modern psyche and the Anthropocene, today totally part of our neurochemical responses in our relationship with the world (infrastructure of the unconscious); Enkidu is wild Nature itself, with the cutting and extinction of the relationship and the consequent pain that this civilisational wound brings to us all; Siduri represents the place where, in humility, we are invited to rescue the potent somatic alchemy of affection and ritual presence as a ground and visceral relationship. The place where we can dance with our monsters, listen to our howling and knead and ferment the emotions we have forgotten.

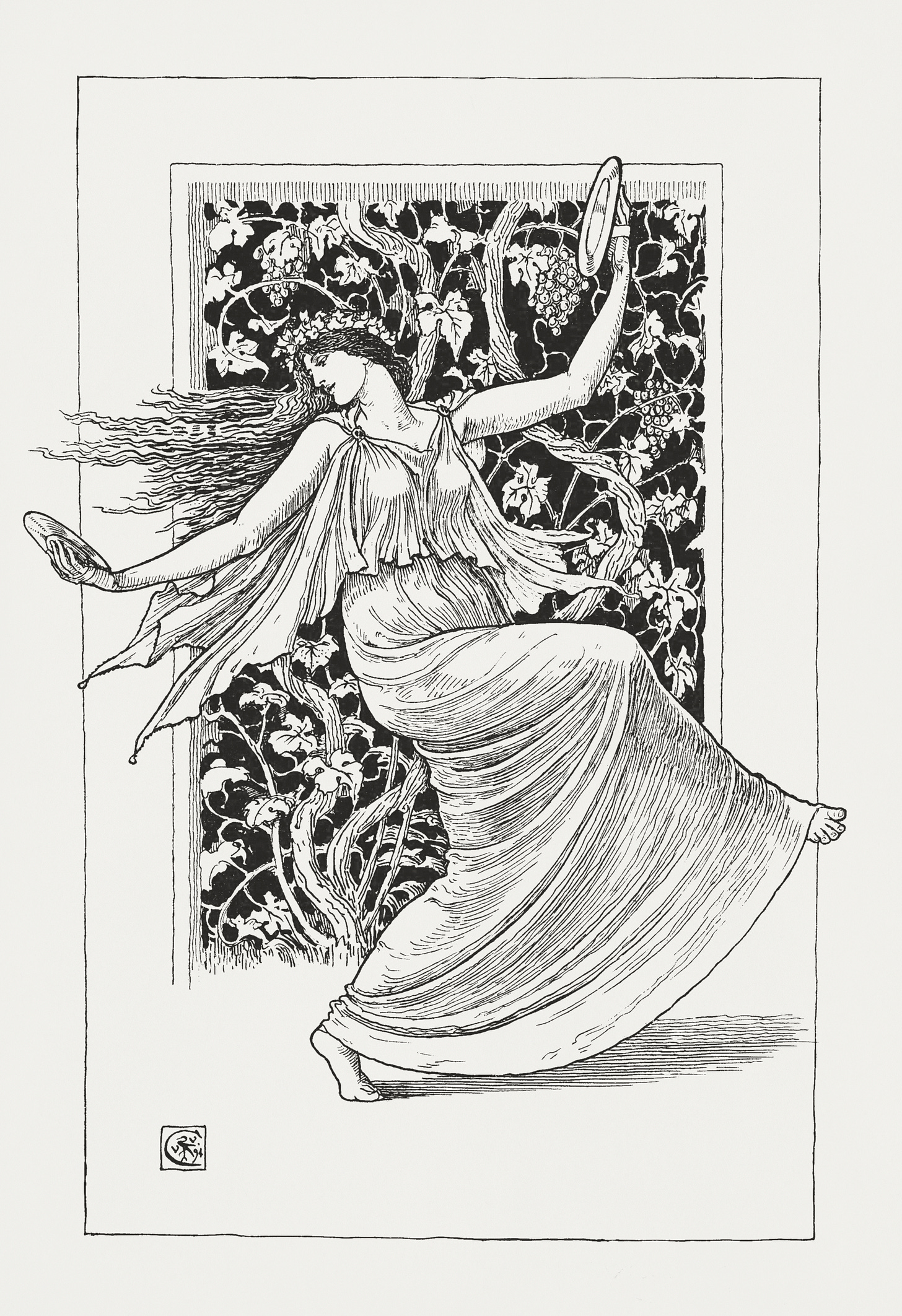

In the story, I wanted to wrap Siduri's sacred presence with sensory voluptuousness, adding the body's movement and the delight of its sacred and chthonic functions. I added details about her place and clarified her tasks as one of the iterations of the Goddess of the Underworld. In the fabulation, I’ve created an image that would evoke and involve the various senses, as it is one of the forgotten keys to the potency of Life’s immanence (contrasting Gilgamesh’s quest for transcendence).

Eco-mythological key - The Garden of Paradise

"We were expelled from paradise," is what our Judeo-Christian legacy whispers to us. A belief that is not shared by the world's native peoples, who state they have never been evicted from the garden of abundance. These original and indigenous peoples actively and with affection co-create with the land all the time, in empathetic and more-than-human ceremonies and rituals that constantly generate the world.

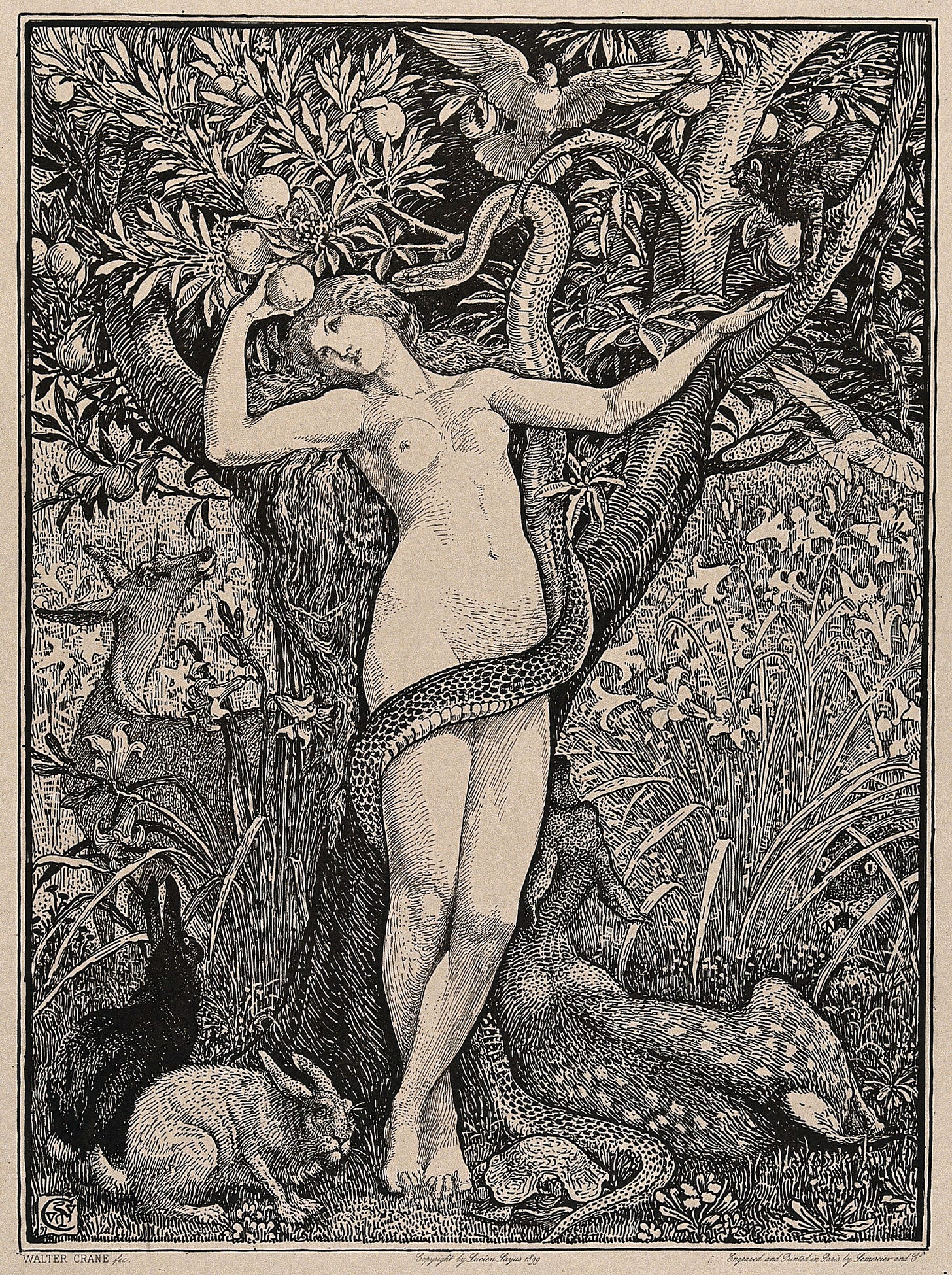

Siduri's description of the garden, which includes a Tree of Life and the serpent guardian, is a valuable first record of an ancient version of Eden, later replicated in the Garden of the Hesperides and, of course, in the monotheistic version of Adam and Eve.

The vine is one of the identifications of the Tree-of-Life-Wisdom-Knowledge, while the fig tree is another possibility due to its layers of sexuality. The fruit of the Tree of Wisdom is accessible to the serpent-goddess, who can hardly be separated from the serpent Siduri, who guards the vineyard of Life and wisdom at the source of the rivers. Wisdom, as the Tree of Life, is also compared to the cedar of Lebanon, the cypress, the palm tree, the oleander or the olive tree. The grape is the symbol of the fruit of wisdom, and the being intertwined with the vine is a reflection of the ancient goddess of the vine and wisdom. An ancestral mythological nucleus is the concept that the vine is the World Tree, a plant capable of encircling the sky, whose fruits are the stars.

This sensory garden of abundance to the west, described to be by the sea and at the confluence of the four rivers, is located at the entrance to the underworld. It is not a place of judgment but of welcome. Not a one-way passage to Death, but a potent and simple place of rest and alchemy. How incredible that we can still access the paradisiacal Garden of Delights in all its potential for transformation and revelation, even with all our burdens, tensions, and disappointments. It's ravishing that an orchard of affection exists on the threshold of the unconscious. A place where travellers between worlds can let go of life's hardships, release the ego's restlessness and desires, and let go of the anxieties and disconsolation of the soul. A place to bring us back to Life.

Eco-Mythological Key - The Tabernacle Goddess And Ophidic Guardian Of The Tree-Of-Life

Siduri is presented as a sābītu, a tabernacle woman. Siduri means "the young woman," and as her Akkadian personal name Šī-dūrī, it means "she is my protection," the young woman who protects me. From a hymn in honour of Ninkasi — an anthem containing the oldest beer recipe ever found, incorporated into Siduri's tale; Ninkasi also means "mistress of intoxicating drink," being the consort of the "good vine" —, we know that both were daughters of Nin-til, the Mist Lady, queen of fresh underground water, and Enki (Ea), her king. Ninkasi, "she who fills her mouth," and Siduri, were daughters, or doubles, of the Goddess of Life. Siduri, the tavern wench, probably a priestess of Inanna-Ishtar, is part of the ancient alchemical feminine tradition of fermenting beer and wine, in domestic kitchens. Around 2050 BC, the fermentation of beer became commercial and women were forbidden to do it.

Since time immemorial, wine and alcoholic beverages, in general, have been the symbol of Life and the gateway to ecstatic states — in Persian "liquor of youth" and Sumerian "Tree-of-Life." Because of the mythical and geographical connections, we can't forget the profound relationship between the nectar of the gods, Soma, a mysterious and sacred Iranian and Hindu drink with the power of immortality, and the wines of ancient thorny vines. W. F. Albright writes that the medicinal, antiseptic and stimulating virtues of wine, known since antiquity, find expression in the Arabic designation 'healer' or 'medicinal herb'. As a healer and invigorator, as a restorer of fertility (aphrodisiac), and as a portal to expanded states of consciousness, wine was worshipped by poets and priests alike. The Sumerians called a particular serpent the "serpent of wine."

The deities of the vine bring the serpent in their accompanying entourage, and the spirits of alcohol, children of Ninkasi, Siduri's sister or double, are called "the snake enchanters of the sky."

Looking deeper, Siduri-Sabitu is part of the eco-mythological cycle of Inanna-Dumuzi / Ishtar-Tammuz, the Sumerian cycle of vegetation and pastoralism. Dumuzi/Tammuz dies every year only to be resurrected, symbolising the cycle of plant life, being the husband or lover of Inanna-Ishtar. A family pantheon that reflects the seasonal cycle of vegetation and Nature, where we find virgin goddesses and deities of wisdom and healing, of the vine and Life. According to W. F. Albright, the name Siduri cannot be separated from Sirtur, the mother of Dumuzi-Tammuz, which means "maiden, virgin." Siduri is "the veiled one," the virgin and bride.

Parallel to the fairies who dance in the fountains and glades, veiled and invisible to all but the chosen few. Let's also remember Nin-til, the Lady of the Mist, queen of fresh underground water, a link to the mythology of mist and clouds. The chthonic and mythical complex of snakes and vines, as well as being linked to the fertility of seeds, has a deep connection to the weather, spring rain, and the fertilising winds.

In an ancient version, Siduri was the goal of Gilgamesh's search for Life, the goddess, or nymph guardian of the fruit and grapes and the source of Life at the sacred confluence of the four rivers. W. F. Albright (1920) mentions that in the series of incantations, Surpu, II, 172, she is called "goddess of wisdom, genius of Life."

Let's not forget that in the land of dates, there is a clear differentiation between unisexual and bisexual vegetation, which encourages the myths of couples/siblings/mothers-sons as divine facilitators of the earth's fertility. It's essential to recall the mythology of ecological observations and wisdom that translates the source of the fecundity of seeds into a marriage between the sky-father and the earth-mother. Or between the god of the flood and the goddess of the earth. In this conception, the goddess loses her virginity by becoming pregnant with plant Life.

The name Siduri has broad and deep connections with the chthonic powers of regeneration and fecundity of the underworld, the womb, and the uterus. In the original poem, which is about 5,000 years old, the passage: "Siduri looks at him and locks the door with the bolt, hurriedly flees to the roof. "Why did you look at me and lock your door with a bolt? I'll break the door, I'll break the bolt!" — says the angry man with the flesh of a god and a man," is repeated in the story of the Goddess Inanna's descent into the underworld, thus confirming Siduri's chthonic powers. It is no coincidence that her garden of abundance, knowledge, and sexuality is on the edge of the underworld, the ancestral world of the dead. When the mythical Goddess of Fermentation Siduri still has a voice, in mythical terms, Death has not yet been separated from Life, forming part of the same cyclical complex: the paradoxical wisdom of abundance that includes decay, decomposition, rot and putrefaction, which alchemically ferment back into abundance, nourishing Life.

She is the legitimate Goddess of the Vineyard, a snake-goddess, of Life and Wisdom. As a virgin nymph, she is one of the serpent nymphs, ginns, or Moors, who appear as serpents in the oldest references. W. F. Albright notes that the Arabs called a serpent 'ildhat, 'goddess' and modern Syrians still call it a 'maiden.’ Similarly, the Egyptian hieroglyph for "goddess" is a serpent. Bringing the importance of shedding skin as a mythological motif. We can't ignore the association between the vine and the serpent in the fact that the vine resembles a serpent. The serpent coiled around the Tree of Life is common, in the form of the caduceus. Nor can we ignore the similarity between the ancient Sumerian mu, 'serpent,' and mus, 'Tree,' a reflection of the association between the Tree of Life and the serpent. In Anatolia, where the two were most closely linked, the serpent was the protective genie of the vine. The Egyptian ka and the Roman genni were also personified in serpents.

We can't disregard the deep connections to the later ecstatic gods, Dionysus and Bacchus, guardians of the vine's alchemical secrets, sexuality, and fermentation. Siduri's links to Isis, Astarte, and Calypso are also evident. The description of Siduri is rooted in these later deities, as is the reference to the sea throne also shared by Astarte and Isis, the Egyptian-Phoenician ocean ladies.

The nymph Calypso, who lives in a cave surrounded by lush vineyards laden with grapes, is able to grant immortality, obtained by taking a swig of heavenly ambrosia, in a metaphor for Soma, and fermented drinks taken in a ceremonial context, just as Siduri invites.

Siduri And Gilgamesh

As we have already seen, Siduri, before being belittled, silenced and forgotten, knew the ritual and alchemical secrets of Death and Life, Mourning and Love. Not as a superior, judgmental or blaming entity, but as a warmth and embrace that invites us to enter paradise so that we can rest there and celebrate Life itself, transforming and relating in humility.

In the oldest versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh, it is said that she would have been his ultimate goal, and her wisdom the catalyst for the hero's transformation back to Life, shattering his illusions of superiority and immortality.

Over time, Gilgamesh's story changes, causing him to aggressively neglect what he perceives as inferior knowledge. He refuses to let go and compounds his self-importance and illusion of exceptionalism in the violent journey to master Life and deny Death. Thus, he breaks the cycle of abundance, transforms the landscape into a salty wasteland, and lays the mythical foundations of the Anthropocene.

[>Part 1 here<] [>Part 2 here<] [>Part 3 here<]

Siduri’s Nectar

Fermented Wisdom at the Edge of the Underworld

These posts have been updated and edited in a printed book.

At the misty thresholds where life ferments into death, and death feeds new forms of life, stands Siduri. Forgotten goddess, veiled innkeeper, alchemical oracle. Before she was erased and reduced to a mere roadside distraction in the Epic of Gilgamesh, Siduri was a guardian of paradox and pleasure, an elder of ecological wisdom and sacred hospitality.

In this mythopoetic and eco-relational text, Siduri’s Nectar distills an ancient dream into contemporary ferment. Woven from years of study, ritual, grief, and dream, Sofia Batalha reclaims Siduri’s presence from the margins of myth and invites readers into a sensual, cyclical ecology of mourning and renewal.

Through storytelling, dreams, etymologies, lamentation, and the symbolic nectar of fermentation, Siduri’s Nectar offers an invitation to sit on the warm stone beside the veiled goddess, to sip from her cup, to mourn what must be mourned, and to feel your way, again and again, back into life.

This is a book for those: tending grief that won’t resolve into solutions; composting illusions of control and superiority; dreaming with the earth, not above her; seeking an embodied mythic literacy beyond patriarchal and extractive logics.

References

Abusch, Tzvi. Male and Female in the Epic of Gilgamesh: Encounters, Literary History, and Interpretation. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015.

Albright, W. F. "The Goddess of Life and Wisdom." The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, vol. 36, no. 4, 1920, pp. 258-294. The University of Chicago Press, https://www.jstor.org/stable/528330.

Barron, Patrick. "The Separation of Wild Animal Nature and Human Nature in Gilgamesh: Roots of a Contemporary Theme." PPL - EBSCO, 2002, pp. 377-394.

Brown, Adrienne Maree. Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good. Edited by Adrienne Maree Brown, AK Press, 2019."

Climate Change: From Gilgamesh to Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy." The Marginalia Review of Books, April 22, 2022, https://themarginaliareview.com/climate-change-from-gilgamesh-to-hitchhikers-guide-to-the-galaxy/. Accessed September 30, 2023.

Dijk-Coombes, Renate M van. "'He Rose And Entered Before The Goddess': Gilgamesh's Interactions With The Goddesses In The Epic Of Gilgamesh." Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages, vol. 44, no. 1, 2018, pp. 61-80. Stellenbosch University.

Dolph, Steve. "The Nature of Our Ruin: Part 1 - PPEH Lab." PPEH Lab, 17 December 2015, http://ppehlab.squarespace.com/blogposts/2015/12/17/the-nature-of-our-ruin-part-1. Accessed September 30, 2023.

Grahn, Judy. "Ecology of the Erotic in a Myth of Inanna." International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, vol. 29, no. 2, 2010, pp. 58-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2010.29.2.58.

McClellan, Andrew M. "Opinion: A Warning from the Dawn of History Echoes in Today's Debate Over Climate Change." Times of San Diego, October 9, 2021, https://timesofsandiego.com/opinion/2021/10/09/a-warning-from-the-dawn-of-history-echoes-in-todays-debate-over-climate-change/. Accessed September 30, 2023."

(rude diagnostic exercise) - Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures." Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures, https://decolonialfutures.net/modern-colonial-infrastructures/. Accessed September 30, 2023.

Sentesy, Mark. The Ecological Predicament Of The Epic Of Gilgamesh. Draft ed., 2022.Sin-leqi-unninni. He whom the abyss saw: Epic of Gilgamesh. Autêntica, 2017.

Verlie, Blanche. Learning to Live with Climate Change: From Anxiety to Transformation. Routledge, 2023.

West, Martin Litchfield. The east face of Helicon: west Asiatic elements in Greek poetry and myth.

I’m working to make all posts open to everyone. Paid subscriptions help support the depth of this research, allowing these narratives to continue gestating outside institutional and market demands. You’re invited to support if you feel called, but your presence here, as a living witness, is already part of the story.

Honor hystera. Re-member. Response-ability. (Un)learn together.

This is not a hero’s journey. This is a remembering.