Dear reader,

Please note that the content shared here on Substack will differ from what appears in the printed book. While many of the themes, stories, and inquiries may echo across both formats, the book itself has undergone a thorough process of review, editing, refinement, and expansion. In that sense, the printed version holds a more curated, deepened, and embodied iteration of the work.

Think of the Substack as a living ground, where ideas are still fermenting, evolving, and growing their tendrils. The book, meanwhile, is a vessel, harvested with care, ripened in its season, and offered as a more coherent ceremonial bundle.

With tenderness for the ongoingness of becoming,

—Sofia

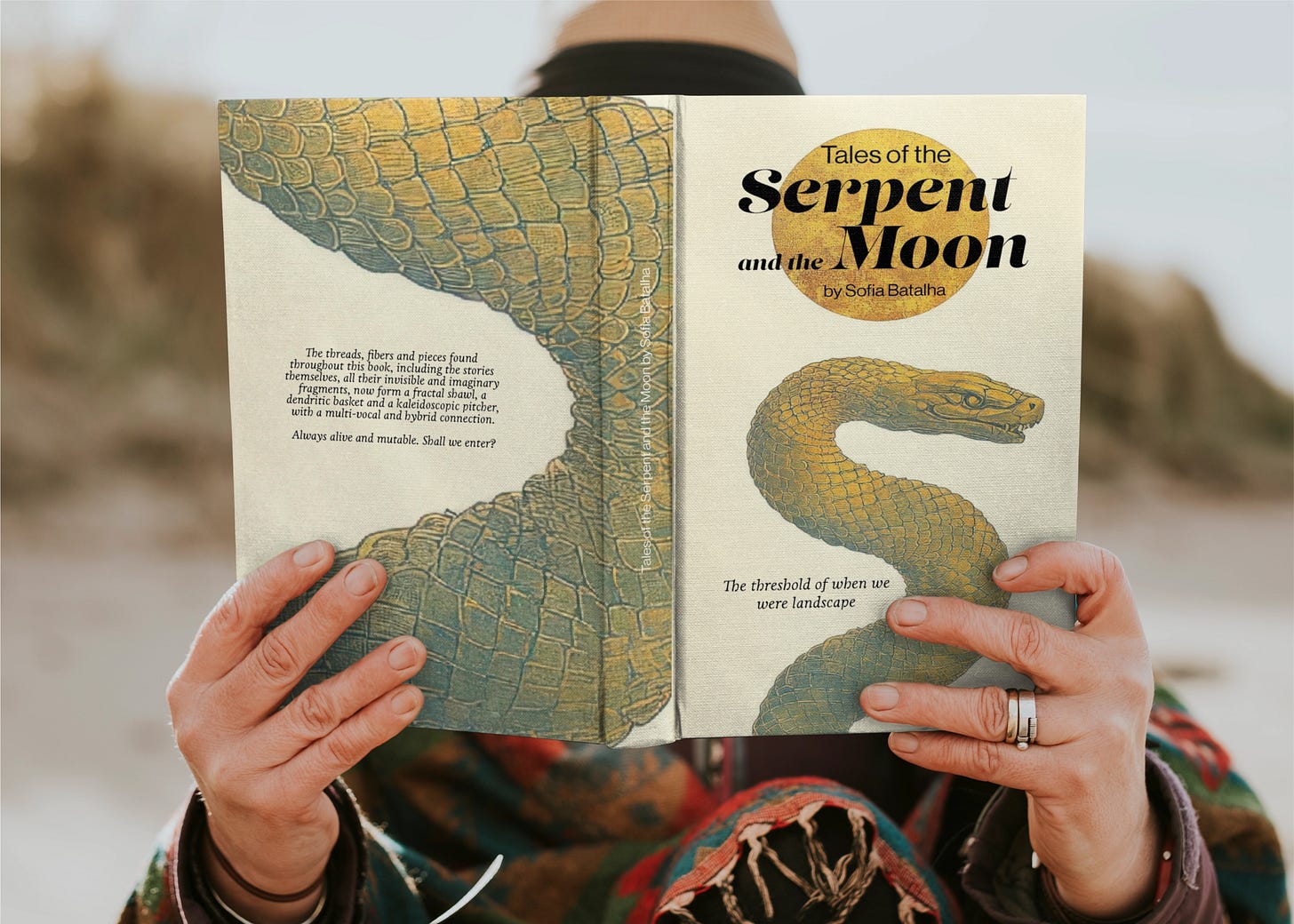

The Tales of the Serpent and the Moon,1 which form the first part of this book, come from my direct access to the subterranean mysteries of the root, where the freshest water runs in the darkness of the earth, surfacing after a groundwork of cleaning up the Christian makeup (in its various facets and phases) of various legends, folk tales, and traditional stories.

The figure of the Washer Mouras,2 mythical beings so present in Portuguese stories, women who wash white clothes in rivers and fountains, are evoked for various reasons. These guardian spirits of the waters are interpreted here not as a legacy of the Moorish culture that fertilized the Iberian territory over eight hundred years, but as archaic and primeval remnants of Genius Locci, or spirits of place, sacred earthly entities later demonized. Each of these entities has its own territory, landscape and history, sharing many symbolic keys, not only throughout the Iberian territory but also across Europe. The legends of serpent-fairy-maidens express the resistance of the indigenous cults, which kept alive the shamanic sovereignty of certain places in free and non-Christianised Europe. One of the resources to learn more about this alternative perspective of the Moorshish enchanted women, not as Moorish legacy, but as much older sacred entities of the territory, is the research work of authors Fernanda Frazão, Gabriela Morais and Aurélio Lopes (see bibliography).

Starting the deep rescue pilgrimage, knees on the ground and hands in the earth, we thus call upon the Washer Mouras, those potent chthonic entities, of ritual baths and washings of purification and ablution, that they may help us wash the stories and tales of their most recent cultural layers, paving the way to their original core.

In 2018, when I started the research and investigation for my book Lugar Feliz (see bibliography), which came out in 2020 by publishing house IN, I recalled and reread many Portuguese folktales and what, I felt, was common across the board: a profound disassociation with the original nature of these ancestral tales, a curation that confined them in linear, mental, religious and moral judgments. This reductive lens constantly renders female characters immature and mutilated of their own inherent power, for whenever any woman retains any power, she is either holy and innocent, or, more commonly, a demon and her actions are naturally destructive or evil, all of them being relatively immature.

In European tales, female characters are generically demonized, and grandmothers are disempowered, having lost their gifts of healing. The malevolent stepmother who replaces the mother and often acts with cruelty, can, in fact, be equated to the serpent in the garden of Eden, and her action to the initiation of ancestral transition rituals and trials of death and rebirth. In these mutilated tales with a linear and moralistic varnish, like the stepmothers, so too have the elderly women lost and forgotten the broad technical expertise of the healers, herbalists, faith healers, midwives, singers, poetesses or sowers, showing a superficial, immature and extremely limited image of the feminine.

The original version of the tales has been confined over centuries by patriarchal prejudices denying women victory, insight, or sovereignty, systematically portraying them either as helpless victims in need of rescue or as demons to be obliterated. Although the saintly and innocent Virgin has maintained an important role for the feminine in Christianity, her archetype is clearly an incomplete and one-sided representation because, as Marie Louise Von Franz writes, she "encompasses only the sublime and light aspects of the divine feminine principle." In fairy tales, however, the fuller pre-Christian expression of feminine spirituality occurs, including the deep feminine of crucial darkness in cyclical phases, and one can find its remnants in the not completely sanitized versions of the tales.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cosmic-Chthonic Cartographies to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.