I found myself there. I went there again and again, without knowing it. Night after night, I made my way to that mysterious place.

Again and again, she took my arm, and we walked together through the trees and bushes, under a living, black, nourishing ground. Spectres of colour shimmered from the ground to the sky; flowers glistened, insects with glossy bodies buzzed and sparkled, and birds with colourful, flaming feathers sang, filling the air. The water and the breeze drummed rhythmically on the stones, dripping and passing through the place.

Here, in the arcane and primeval garden-temple, at the confluence of the four rivers, right on the edge of the underworld, the trees bend under the weight of juicy and colourful fruit, the bushes burst with colourful berries and the flowers dance in the wind. Flavours and aromas mingle in a dripping, abundant abundance. In this garden, the ancestral carobs, cedars, figs, olives, raspberries, date palms, apple trees, pomegranates and grapevines, sweet, ripe and fruitful, are born from a dark ground that pulses with death, which nourishes life. The sacred fermentation that transmutes.

"Sit on that stone," she says. And when I lowered myself to sit down, I was carried away by the enchantment of the ground. Black, dark, udder and seminal. A primal, alchemical belly that transforms mourning and pain into life and love. It breaks down torment and digests bitterness. It's a boiling, living ground of death, an abyssal interstice. The ground and the heart pulsate together. The floor comprises the nourishing decomposition of shards, pains, sorrows, transformations, passions, and challenges. But also of joys, because it is the fertile ground that allows regeneration. A powerful and porous place that embraces and transforms, a passage and respite between dimensions of rest and wandering, the ultimate pause on the road to death or the rescue of life.

I am awoken from this fascination by her hand's soft, warm touch, which offers me a sweet, fermented drink—nectar that warms my chest, welcoming my fragility and vulnerability. She unfolds in a presence that offers a lap, attention and tenderness, listening and care. My critter body is taken up and enveloped in this invitation and embrace, this sacrament of coming back to life. It convulses and stirs. It yields.

When Siduri invited me and fertilised my dreams, I drank from her cup again and again. Night after night I accepted the invitation to swallow the nectar, and to spread the ambrosia like an ointment over my body.

That's how Siduri made herself known; she welcomed and transformed me in an immemorial ritual of changing skin.

Eco-Mythology of Nectar

{nectar, ambrosia and elixir}

Nectar comes from the Latin nectar, from the Greek nektar, the name of the drink of the gods, which may be an ancient Indo-European poetic compound of nek- "death" (from the root *nek- "death") + -tar "overcoming", from the root *tere- "to cross, pass through, overcome".

Ambrosia, comes from the Latin and Greek ambrosia, "food of the gods", "divine", probably literally "of the immortals", from ambrotos "immortal, imperishable"; but also linked to rubbing the dead.

Elixir, from Arabic al-iksir "the philosopher's stone", most likely from Late Greek xerion "powder for drying wounds", from xeros "dry". Later, in medical use, for "a tincture with more than one base". The general meaning of "strong tonic" dates from the 1590s.

Nectar and Ambrosia have been associated with wild honey, a familiar ingredient since arcane times. Some authors equate ambrosia with bread (a food product of fermentation, like beer, wine or cheese), but ambrosia was used as an ointment or cleaning application. It was also thought of as a liquefied fat (marrow and fat) with the analogous vegetable sap, olive oil, as an alternative. It was an offering to the gods, "something to anoint".

Ambrosia is used by Hera as a cleansing substance for her own body, who, after sprinkling her skin with ambrosia, 'anointed herself with perfumed ambrosial oil'. It would, therefore, be natural to say that the oil used by the goddess as an ointment was fit to be eaten; in other words, it was of the highest quality. The Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite suggests it was liquid food, just like Sappho. In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, the goddess feeds the baby Demophon, making him grow 'not with corn to eat or milk' taken through her lips, but "anointing him with ambrosia", it was believed that by anointing with fat or oil, the liquid of life was infused through the skin.

Olive oil is one of the possibilities for ambrosia as an edible divine ointment: "To torment Tantalus, over his head tall trees hung their fruit, pear trees and pomegranate trees and apple trees with shining fruit and sweet fig trees and olive trees in bloom, which when the old man stretched out his hands to grasp them, the wind tossed into the dark clouds."

Where did the gods get the ambrosia? If the question were asked, the simplest answer would be that somewhere, inaccessible to ordinary mortals, it sprouted or grew as a plant with oily sap, like the olive tree or myrrh. Homer tells us nothing more about it, except that the river-god Simoeis "brought up ambrosia for Hera's horses to eat"; and that doves carried ambrosia to Zeus on Ulysses' way back from Okeanos and the underworld. Euripides thought of the "fountains of ambrosia", in the land of dusk, at the ends of the earth, "by the bridal couches of Zeus' halls, where the divine, life-giving earth increases the happiness of the gods". The land of dusk, on the river Okeanos, at the ends of the earth. It must be near the garden where Siduri took me in.

The nectar must be the divine equivalent of the other form of food that men have seen fit to offer the gods —wine or beer, both fermented drinks prepared by the Goddess Taverner in the Garden, who mashes them with honey and dates. The allusions imply that it was liquid. Like wine, it is "mixed" and poured out for the gods. Sappho recounts the libation of ambrosia at a wedding, which suggests it was wine, but a liquid mixed with pure water, olive oil and a collection of seeds. But there are also references to a flask of oil, as when, at Helen's wedding, the Spartan maids say that they go to Helen's tree and pour libation, "dripping liquid from a silver flask".

Ambrosia takes shape as oil enriched with other ingredients, and nectar as enriched wine, like an ancient drink/food where cheese, barley and honey are mixed with wine. Or like the fat offered to the gods by men (to which we have linked ambrosia) enriched with barley grains, as Siduri kneads in the pit of the ground of death and life.

In the Homeric Hymns, the Greeks preserved these ancient sacraments, ambrosia, similar to oil or fat, and nectar, similar to wine. For Aristophanes, ambrosia is "poured" but eaten, while wine is described as a "drop of nectar". The ambrosia is not only offered by men to the gods but is also rubbed on the bones of the dead; the nectar is not only with the wine offered by men to the gods but is also poured on the bones of the dead. This opens up the deep relationship of the much earlier and arcane guardian Siduri with fermented drinks, on the brink of the underworld.

Honey also appears in relation to the dead. "For all the dead", Ulysses "poured first with a mixture of honey (honey with water or milk, or wine), then with sweet wine, and the third time with water and sprinkled with white barley". Honey seems to have been a substitute for wine when it was inconvenient. The wine was "as sweet as honey" and the honey was mixed with the wine.

Ambrosia is an oily or fatty liquid, and nectar is the watery liquid of life. In ancient Persian belief, the food of immortality consisted of the celestial haoma's sap (like the vine's juice) and the marrow of the dead ox. Later, Mithraism taught that the god will come to earth and the dead will rise from their graves. He will sacrifice the divine bull and, mixing its fat with sacred wine, offer the cup of eternal life to the righteous. The same elements can be seen in Christian baptism, such as pure water and blood-wine. Water and oil were used in the earliest forms of the sacramental rite.

These sacraments, whether in ointments or fermented drinks mixed with seeds, water or honey, are part of the Mediterranean landscape and ecosystems. Their composition and mix are not a detail, but powerful eco-mythological, living and contextual keys.

The ingredients —whose etymology comes from "to walk and to go"— are more-than-human entities of these territories. These powerful symbols of connection between dimensions and beings still make up our landscapes and food. With or without sacrament, they are still part of us. Bridges to ancient gods and mythical places that our bones remember: olive oil, honey or wine, from water, milk and seeds.

Just like Siduri, who brought me to these mythical lands of death and life and pulled me back to life with her lap, drink, and ointment, we can remember together—returning to the multiple and profound stories of the ecosystems surrounding us—to the immanent and eco-mythical abundance that anchors and welcomes us.

[>Part 1 here<] [>Part 2 here<] [>Part 3 here<] [>Part 4 here<]

References:

The Origins of European Thought About the Body, the Mind, the Soul, the World, Time and Fate, R. B. Onians - p.311 to 318

https://www.etymonline.com/

Written in Portuguese here: https://serpentedalua.com/o-nectar-de-siduri/

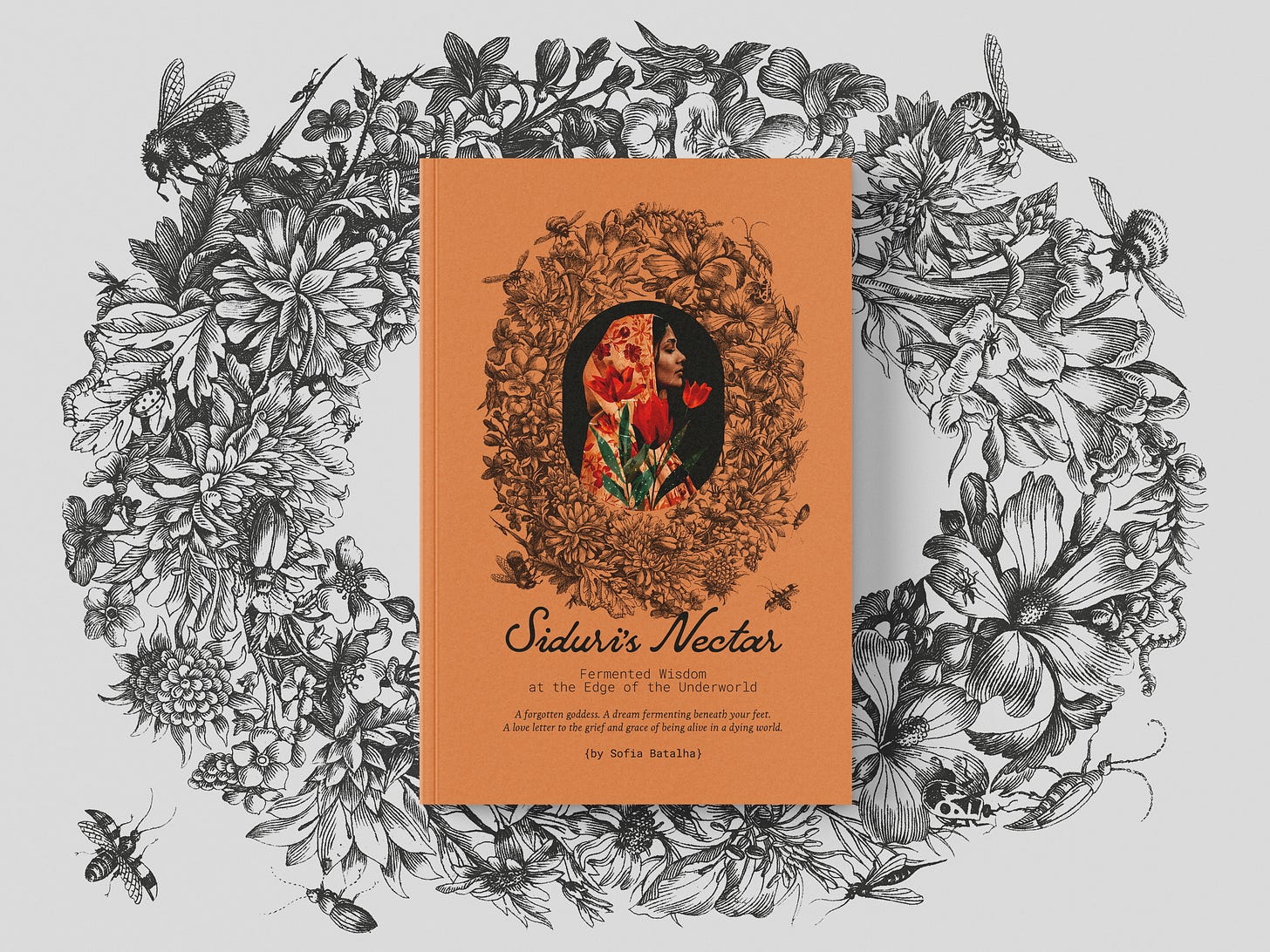

Siduri’s Nectar

Fermented Wisdom at the Edge of the Underworld

These posts have been updated and edited in a printed book.

At the misty thresholds where life ferments into death, and death feeds new forms of life, stands Siduri. Forgotten goddess, veiled innkeeper, alchemical oracle. Before she was erased and reduced to a mere roadside distraction in the Epic of Gilgamesh, Siduri was a guardian of paradox and pleasure, an elder of ecological wisdom and sacred hospitality.

In this mythopoetic and eco-relational text, Siduri’s Nectar distills an ancient dream into contemporary ferment. Woven from years of study, ritual, grief, and dream, Sofia Batalha reclaims Siduri’s presence from the margins of myth and invites readers into a sensual, cyclical ecology of mourning and renewal.

Through storytelling, dreams, etymologies, lamentation, and the symbolic nectar of fermentation, Siduri’s Nectar offers an invitation to sit on the warm stone beside the veiled goddess, to sip from her cup, to mourn what must be mourned, and to feel your way, again and again, back into life.

This is a book for those: tending grief that won’t resolve into solutions; composting illusions of control and superiority; dreaming with the earth, not above her; seeking an embodied mythic literacy beyond patriarchal and extractive logics.

I’m working to make all posts open to everyone. Paid subscriptions help support the depth of this research, allowing these narratives to continue gestating outside institutional and market demands. You’re invited to support if you feel called, but your presence here, as a living witness, is already part of the story.

Honor hystera. Re-member. Response-ability. (Un)learn together.

This is not a hero’s journey. This is a remembering.

That would be nice. You are the busy one- offer some suggestions

What a rich and fertile account!

In Indian scripture, it is said that the food of gods (soma) has no effect on humans - even if they could access it.