Dear reader,

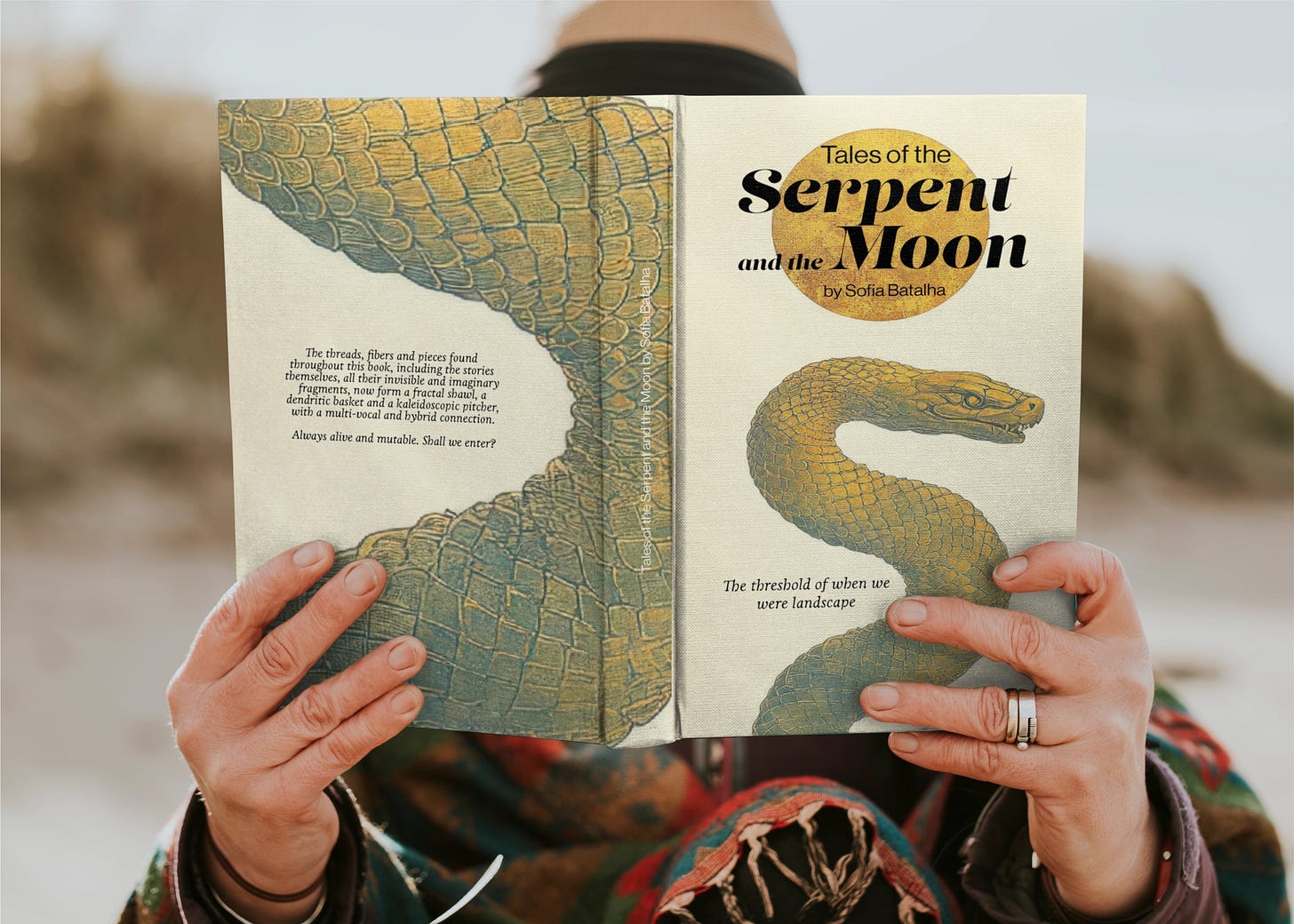

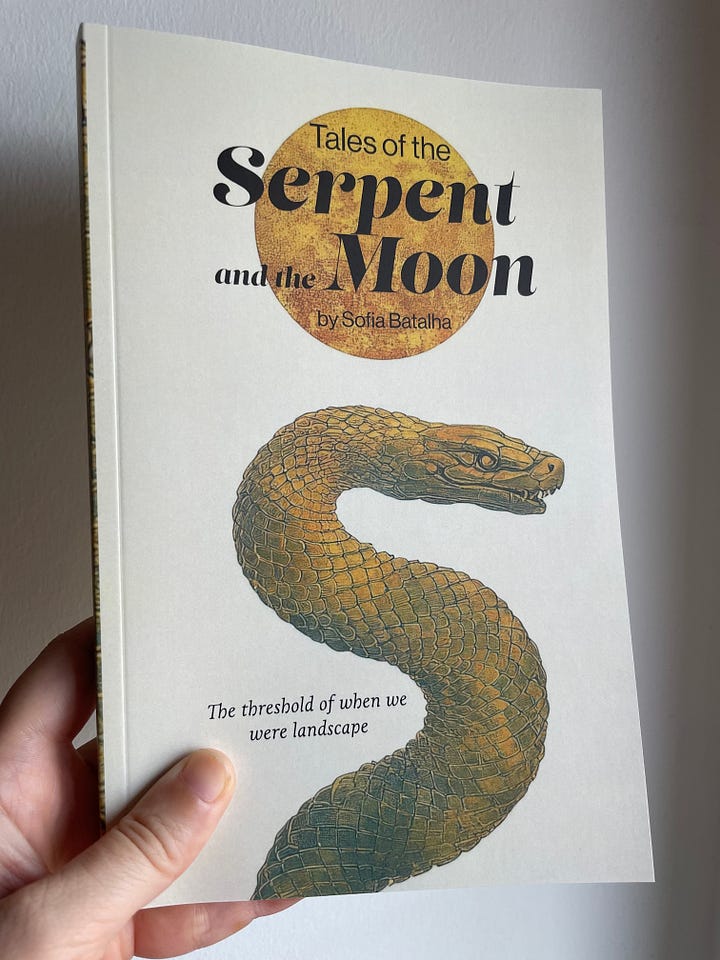

Please note that the content shared here on Substack will differ from what appears in the printed book. While many of the themes, stories, and inquiries may echo across both formats, the book itself has undergone a thorough process of review, editing, refinement, and expansion. In that sense, the printed version holds a more curated, deepened, and embodied iteration of the work.

Think of the Substack as a living ground, where ideas are still fermenting, evolving, and growing their tendrils. The book, meanwhile, is a vessel, harvested with care, ripened in its season, and offered as a more coherent ceremonial bundle.

With tenderness for the ongoingness of becoming,

—Sofia

The Story

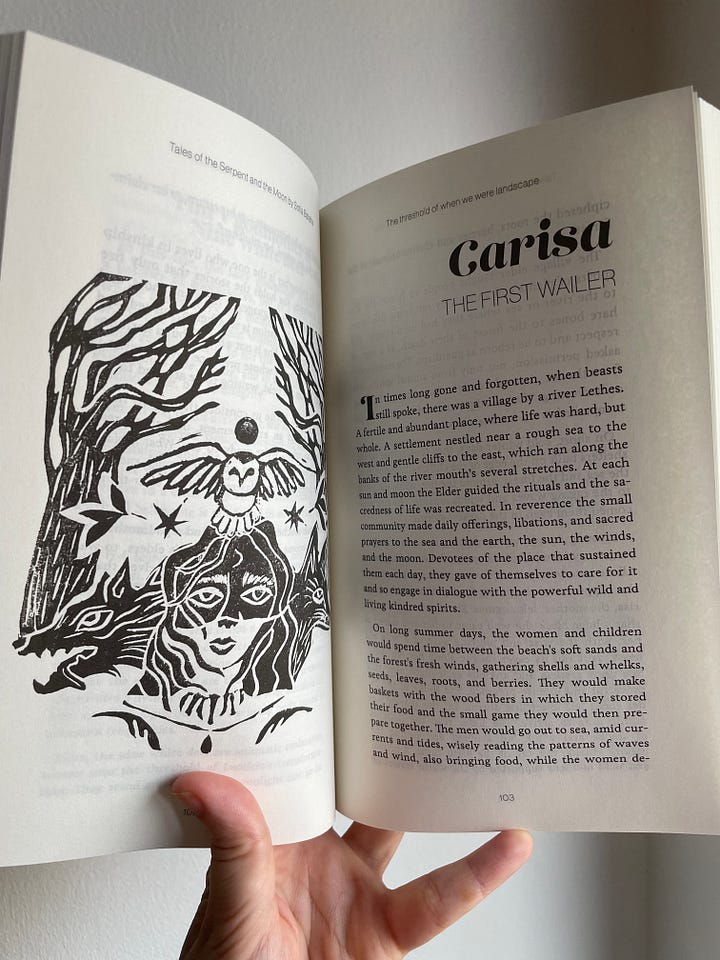

In times long gone and forgotten, when beasts still spoke, there was a village by the river that is nowadays called Letes. A fertile and abundant place, where life was hard, but whole. A settlement nestled near a rough sea to the west and gentle cliffs to the east, which ran along the banks of the river mouth’s several stretches. At each sun and moon the Elder guided the rituals and the sacredness of life was recreated.

The small community took charge in body and reverence of the daily offerings and libations, and the sacred prayers to the sea and the earth, the sun, the winds, and the moon. Devotees of the place that sustained them each day, they gave of themselves to care for it and so engage in dialogue with the powerful wild and living spirits.

On long summer days, the women and children would spend time between the beach's soft sands and the forest's fresh winds, gathering shells and whelks and seeds, leaves, roots, and berries. They would make baskets with the wood fibres in which they stored their food and the small game they would then prepare together. The men would go out to sea, amid currents and tides, wisely reading the patterns of waves and wind, also bringing food, while the women deciphered the roots, berries and elusive animals of the forest.

The village elder taught people to honour the spirits of plants and animals by returning fish bones to the river or sea where they had been caught, and hare bones to the forest of their death, as a sign of respect and to be reborn as guardians. The community asked permission, not only from the spirits of the animals, but from the spirits of the sea, the rocks and the forest, before hunting or harvesting. The sacred ground’s support accompanied every need or transformation.

On short, cold winter days, they took refuge in the shelters built on the edge of the cliffs, telling stories of the sea and the forest around the fire, while listening to the raging waves and winds outside. The fire welcomed them even in the darkest storms.

A young couple was expecting their first child, a pregnancy blessed by the spirit of the winding river. All necessary ceremonies were performed to ensure the happiness of the young family. Nevertheless, Carisa, the mother, felt anxious. She dreamt every night that a huge black she-wolf came to her and stared at her, with the wise and piercing gaze of a wild old beast, as it ran its eager tongue along her whiskers. She grew restless and anxious each night over this powerful and intense presence. She spoke to the Elder about her unsettling dream, but the answer was taking long to arrive. The Elder read the patterns of smoke and wind, but avoided deciphering the dream. Finally, the day of the birth came, a primal and wild moment supported by the warm waters of the summer river. A beautiful boy was born, plump and strong, who quickly cried and suckled. The wind brought good omens for that family, and the Elder rejoiced, seeing that the newborn had his coif intact on top of his head. Carisa always tucked her baby in, full of tenderness and affection. She quickly adapted to the presence of that little being close to her, for they were part of each other.

On the twelfth day after the birth, the men set out to sea again, and Carisa slept alone with her son that moonless night. It was a restless and intense night, uncomfortable and without a proper resting position. Carisa felt watched and hectic. In the middle of the night, she awakens startled by a howl that cuts the air. Right there. Terrified, she instinctively searches for her son's warm and soft body, but she doesn't feel him near her. She can no longer hear his breathing or smell his scent. Panicked, she searches everywhere, groping in the dark night, while in her throat a knot of pain and fear forms and is released all at once in a deafening shriek, waking up the rest of the village.

The Elder, who had been keeping vigil in the dark of night, realises that all her fears have come true and that the moment of Carisa's initiation has arrived abruptly. She rushes to meet the young mother and, lovingly putting her arm around her waist, takes her at that very moment to the edge of the forest and recites to her: “Remember! Black is the colour of womb and tomb; we meet at night, under the dark moon. White is the colour of bone and ash; to speak with the dead we bathe and fast. Red is the colour of blood and death; we rub the bones and give them breath. Blood is holy water, life force and ancient wisdom.” The Elder continues, hurried yet wise, "To walk between worlds and learn the languages of the beasts and the spirits of the stones, you must work closely with death, blood and bones. The Great She-Wolf has taken your son, and you will have to go retrieve him, the smoke of the fire has said so. Nothing is guaranteed, but be trusting. Go."

The Elder offers Carisa her claw and necklace of bone, an ancient and powerful talisman, blessing her in farewell. She hurriedly pushes the young mother stumbling into the dark forest. All Carisa takes with her is her fur cloak, her stone knife and a basket, her tools of daily use. Feeling deeply distressed and confused, she wanders through the dark and silent forest, but were it not for her excruciating pain, she would know the path she was taking with each step, for she was still in the area she knew like the back of her hand. Yet, the moment’s turmoil, the darkness of the moon and the loneliness of her agony all contributed to her feeling completely lost and at a loss as to what to do. As she staggers forward, the smooth leafy ground becomes increasingly uneven, with large roots and rocks sticking out of the earth.

Carisa doesn't know where she's going, she moves inexorably through the eternal night to placate her pain. Suddenly, she stops amid the darkness and unknown territory, feeling frightened and watched. Huge yellow eyes are staring her in the face. The wild eyes that have visited her in her dreams. Carisa feels the rough fur run past her thigh with a shiver, and instinctively takes her hand to the bone and claw necklace the Elder offered her as she pushed her into the forest. It is the Great Black She-Wolf awaiting an offering, sitting with her fierce gaze. Carisa takes her hand to her apparently empty basket, and groping around, she finds three nuts, which she offers to the Great She-Wolf. Satisfied, the huge animal whispers to her in a growl: "Black is the colour of womb and tomb, we meet at night, under the dark moon. Follow me." The astonished girl momentarily forgets her pain and tries to follow the wolf's quick steps amidst the dense shadows. The winding path becomes increasingly steep and difficult, and the sounds and smells change in the cold, thin air. She doesn't know how long she's been following the she-wolf, but she loses sight of her with sheer exhaustion, feeling alone and lost once more.

Standing atop the dark mountain she wails and howls at the pain of losing her son and herself. As her body shakes, tears fall to the ground and her cries echo into the distance. Suddenly a muffled, low-pitched sound envelops her, a flapping of great wings just above her head. The White Owl, one of the mountain spirits, lands right before her. Carisa, exhausted, drops to her knees, surrendering to the powerful winged presence, tears streaming down falling on the hard ground and making small green shoots spring up. With her ancient and wild gaze, the Great White Owl leaves a feather at Carisa’s feet, of such an iridescent white that it shines even without moonlight, as she hoots: "White is the colour of bone and ash, to speak with the dead we bathe and fast." Carisa had heard the village Elder telling her that feathers lend wings to fly between worlds, tucked into hair or cloaks: "Feathers connect us to the world of spirits and can carry messages between them," she would say.

The young mother picks up the feather and feels light, floating weightlessly over the mountain. She feels strangely calm and guided; she doesn't know how, but she seems to be flying; the stars seem closer and she hears the rustling of leaves from the trees below. She doesn't know how long she flew, as she must have fallen asleep, lulled by the wind into a magical sleep. She awakens, with what seems to be the rising sun, on a fluffy leaf-laden ground, leaning against a rock, her body all sore and a gash on her forehead still bleeding. It takes her some time to regain her senses and remember how she got there. She vaguely remembers covering her whole body with ash and dancing in the river in the starlight. She also remembers taking her knife and making a quick but painful cut on her own forehead. A convulsion rises in her body at the memory of her missing son, and fat tears spill onto the earth in the calling of that lost love. Her chest explodes in a deep, aching wail as she pounds the earth with her hands, tears spilling onto the ground from which new plants sprout. At that moment, she sees red paws approaching in silence.

Blood red Fox approaches her in a calming, friendly presence. "Red is the colour of blood and death; we rub the bones and give them breath," she tells her. "You have reached the place of regeneration, the primaeval origin of things, the source of the winding river," the Fox continues. "The blood that runs down your forehead that blends with the tears you cry for your son, the sacred water, life force and ancestral wisdom, is the offering that illuminates the path of souls. Follow me," she tells Carisa in her ancient language, heading towards a small opening between the stones. Together, they crawl into the ground, through the depths of the earth, in a maze-like journey, humid, winding and tight, as if a huge Serpent has swallowed them. The girl follows the Fox on all fours, as the consecutive tunnels have no room to stand.

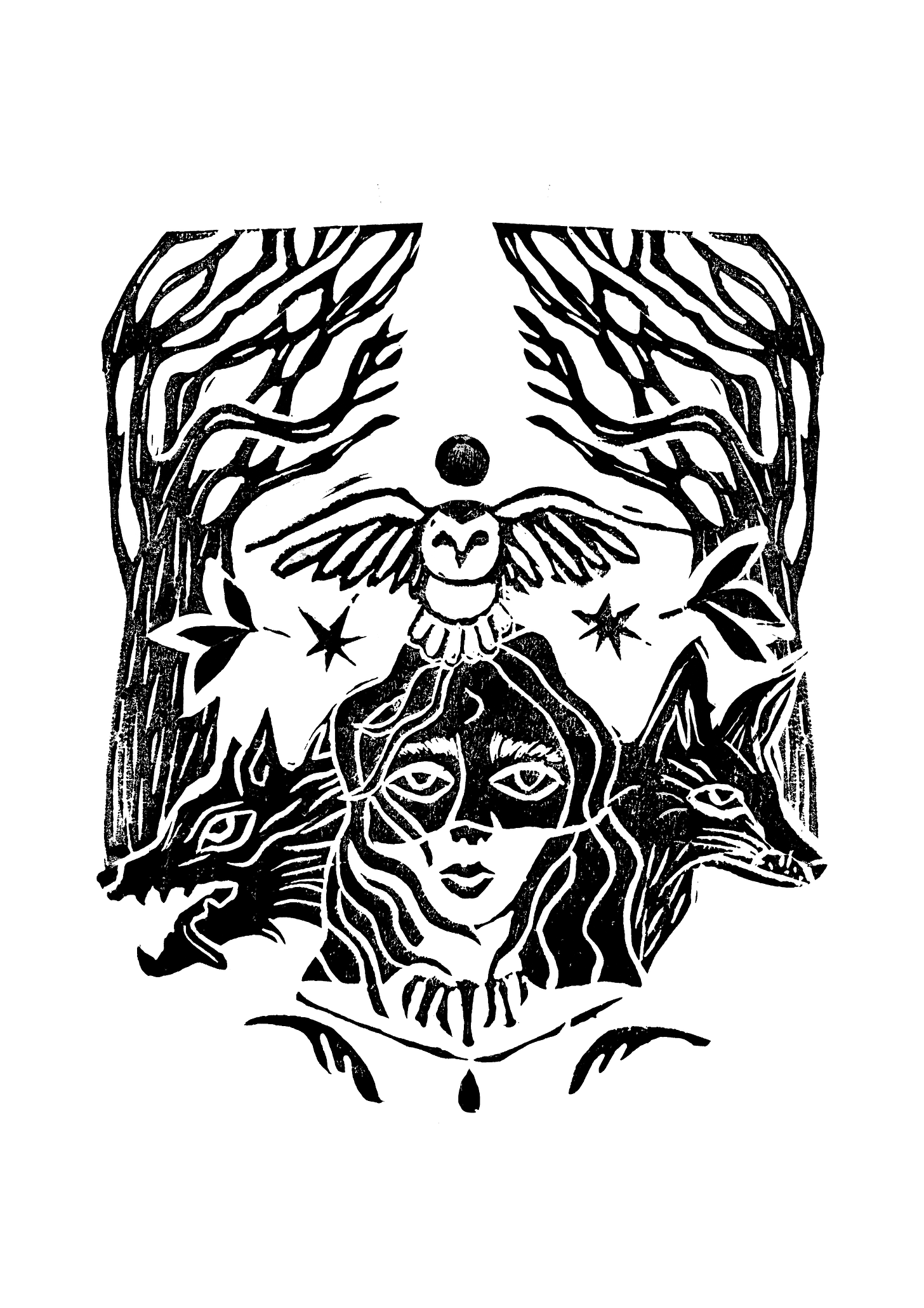

Arriving in a large stone chamber where the bubbling of water threads, stones and memories can be heard, the Fox stops and asks, "What do you have to offer?" Carisa, tired but lucid, finds three pinecones in her empty basket, which she instinctively casts to the ground and says, "I offer myself." The ground and the stones resound with the offering of her body-seed: "You will be Carisa, the first wailer, she who weeps guiding the dead, for you know the secret of regeneration." As she surrenders to the deep ground, in the warm womb of the primaeval Serpent, she finds herself enveloped in an intimate ancestral bosom, which transforms her from within. She feels her bones resting and the pain dissipating, under the watchful eyes of her new guardians: the Black Wolf, the White Owl, and the Red Fox.

The body recovers from fatigue and grief, as she finds her child again in her arms, warm and plump, suckling eagerly. Just like her, he is now branded on the forehead with a half-moon, still fresh and throbbing. Wrapped in an embrace of eternal tenderness, like the night the young mother has gone through, they wake up again in their bed in the village.

Upon waking, nestled against her baby, Carisa doubts everything she remembers about the previous night, the pilgrimage, and the initiation to eternal night. But seeing the pulsating mark on her child's forehead, all doubts are dispelled. The bone necklace she carries, the basket containing the blood-stained stone knife, and the gleaming white feather hold the mystery of remembrance. The men return from the sea that same morning with food and new stories to tell. Still, the greatest story is Carisa's, the first wailer and apprentice to the wild and primordial creatures, surrounded by spirits, anointed with blood and ash, dressed in furs, and adorned with talismans of bone, tooth, and claw. The Elder, meanwhile, vanished in the dead of night.

After the story, please take some time to feel how it relates to you and what unfolds and resonates with your unique context.

Let's breathe.

What breathes through the tale

What follows is not a symbolic interpretation of the tale, exiling it in a single narrative. There is a unique symbiotic dialogue with the tale’s living layers that is yours to feel, sense, and travel through. The following words are mythical, historical, and place transcontextual information that resonates with the tale pulsing realm.

This tale is born out of a need to express ancient voices and has been incorporated with fragments of personal dreams, dreams that bring the basket and the pinecone, but whose details I will leave for another time.

The world portrayed here is archaic, shamanic, and animistic. In this perception of life, weeping, the sacred manifestation of mourning and pain, is part of the regeneration process of life itself, and this is the wisdom recaptured by the main character.

Carisa

Her name, Carisa, comes from Doña Cale, the same as Caliessa (Kali)1. The word Carisa is linguistically related to Cailleach, referred to as the "Mother of All" in parts of Scotland, depicted as an old hag with wild bear teeth and boar tusks, and followed by numerous wild animals; the primal grandmother who holds the profound wisdom of the regeneration of life, in childbirth as the portal to life and death. The resonance of the name "Porto Cale" — port of Cale, evolving to Portugal — ensures the presence of this primal deity in this territory.

Primal Colours - Black, White and Red

To portray the Soul of Death and the longing for the land, the ancient and visceral shamanic reality, I have drawn on Sarah Lawless' brilliant article2, from which the wisdom recited by the elder and Carisa's initiatory animals has been adapted. The use of primal and mysterious colours like white in the Owl's feather and the ash, red in the Fox and the blood and black at night and the She-Wolf, recalls their ritual and ancient importance: they are ritual and archaic colours also present in the German story of "Snow White and Rose Red."

Wolf Child Tale

The story was also supported by the shamanic-rooted tale of the Wolf Child, from the village of D'arque [modern day Darque] on the banks of the River Lima3, recalling that Strabo indicated the River Lima as the mythical River Lethes, the river of oblivion. Also, recalling the symbolism of water as a vehicle for transformation and metamorphosis, and the ancestry of water boundaries that divide worlds and dimensions.

This traditional tale begins on the banks of the river, in the village of D'arque, where a farmer and his wife lived, a kind, young and robust couple. Their hearts were home-bound, for they never went beyond the village grounds. One day, the farmer arrived and found his wife lying beside a newborn baby, and his delight at being a father was great. During the young father's absence, an old woman knocked at the door and his wife invited her in. The old woman looked at the child, muttered a few words and hurriedly left the house.

The child grew up and became strong and active, but always kept silent. His remarkable strength was so noticed, that the village wise woman said there was no doubt the boy was the son of a wolf. His body was carefully examined, and the mark of the crescent moon was found under his arm. The boy disappeared before his parents could take him to the great wise woman of Arrifana. Meanwhile, the wolves became bolder in their attacks on the flocks as winter came. The farmer had set a snare, and one morning, he saw a massive wolf had been caught. He called the village's wise woman, who gathered some pine branches, laid them near the head of the inanimate wolf, and set them on fire. A column of smoke rose like a tower, reaching the top of a hill where some enchanted Moor sorcerers lived; between the wolf and the said Moors4 there was a tunnel of smoke and fire. Then the wise woman chanted some prayers, closing her eyes. When they opened their eyes, the wolf was no longer there and the fire had gone out. In a procession, they went to the cave of the olive trees, led by the woman. They returned home, where they found the boy asleep in his bed. His arms showed signs of bruises caused by the snare's grip when he had been caught in it.

In this tale, smoke appears as the transmuter of the child's fate. In ancient Greek, the art of sacrifice is the same root in the verb thyein or, literally, "to make smoke,"5 inducing visionary clouds, being the origin of the word funeral in Portuguese. There were, in Ancient Greece, many traditions that used smoke as a sacrament (as the previous tale demonstrates with the column of smoke), the smoke-walkers, smoke-splitters, smoke-receivers, as it was an element in the initiation of orphans to the mysteries.

Intuition and the ancient wisdom of darkness

At her initiation and with her stone knife, Carisa draws a half-moon on her forehead and her son's, which is intertwined with the magical power of the third eye. Melusina, a half-woman, half-serpent figure from mediaeval European folklore, attests to her ancestral and pagan nature by having on her forehead a carbuncle, also called the "third eye," "eye of pure thought" or "organ of clairvoyance." Nowadays, the word carbuncle relates to a serious bacterial infection, as one of its symptoms is the appearance of black spots on the body. However, carbuncle literally means coal in Latin, relating also to a semi-mythical black gem from the East Indies, which was believed to be able to glow in the dark - a metaphor for intuition and the ancient wisdom of darkness.

Pinecone

The presence of the pinecone and Carisa's enchanted basket (about the basket, see "The Red Cloak"), which contains what she needs at every moment, are part of my dreamscapes and personal history. The pine cone is the reproductive organ of pine trees, a precursor of the flower, with a very ancient cross-cultural symbolism. The pinecone is a winter fruit, revered as one of the natural forms of sacred geometry, with its spiral pattern in a perfect Fibonacci sequence. Its myth alludes to spiritual enlightenment, a symbol of divine awareness, illumination, or awakening. It is represented in several ancient cultures with the same meaning: the pineal gland or the "third eye," also called the "inner eye," "mind's eye," "eye of the Soul" or "eye of reason." The pineal gland has the name and shape of a pine cone and is located in the geometrical centre of the brain, being closely linked to the perception of light. It modulates waking patterns and circadian rhythms and, apart from the kidneys, receives the highest percentage of blood flow in the body. The pineal gland is considered the "biological third eye" and its sacred symbol, throughout history in cultures worldwide, is the pine cone.

Ancestral rituals

Several ancestral rituals, with shamanic roots, also surface in this tale:

Libations, sacred prayers and devotion to place, ritualised by the Elder.

The giving of fish bones and meat bones as offerings to the place.

The use of animal amulets as keys to travel between worlds.

The whole ordeal and initiation of Carisa: from getting lost in the forest, flying with the feather, purifying herself by wrapping herself in ash and taking the ritual bath, meeting the guardians, entering the belly of the serpent, and the final rescue of the wisdom of mourning.

The importance of following the advice of animal guides, as wild spirits.

Witches flight

During her initiatory journey, Carisa flies using the iridescent white feather of the owl, and this is a recurring theme: the night flight of witches. Shamans consider it a reality, but in the eyes of later mainstream instituted religions, it is seen as a diabolical illusion. Researcher Claude Lecouteaux notes that the entirety of ecclesiastical literature is full of debates on the subject, leading to the connection of the flight with the death sentence of people suspected of night pilgrimages. Originally, night flying was part of a complex set of agrarian and pre-agrarian rituals, intended to ensure the prosperity and fertility of the village or family community.

Primeval guides

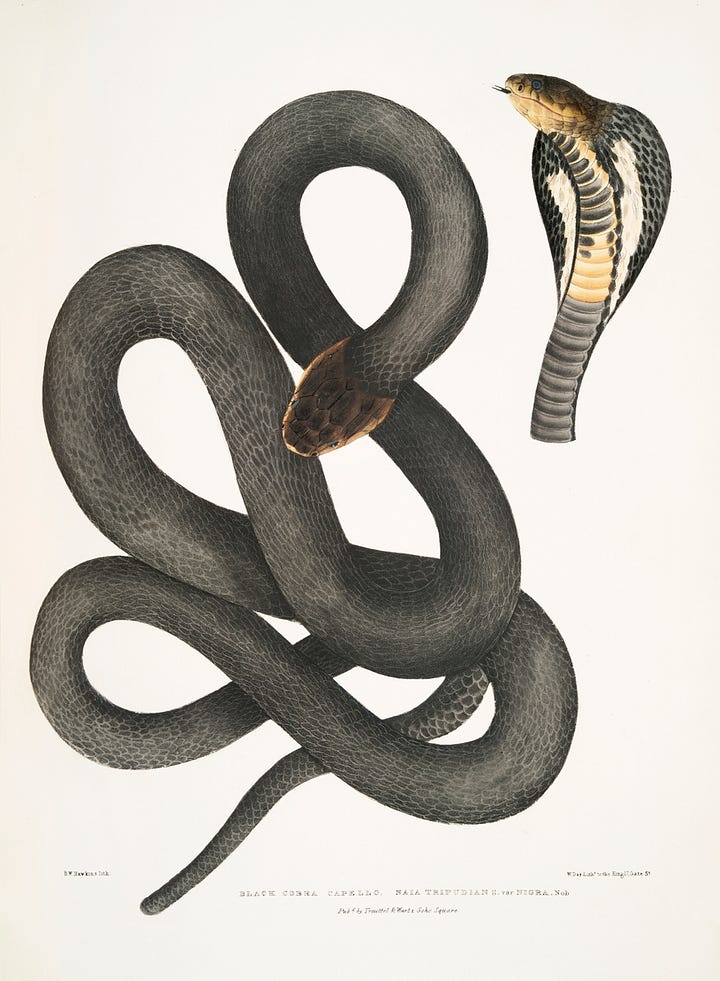

We also have the presence of three archaic and essential guides: the She-Wolf, the Owl, the Fox, and the essential presence of the great Serpent. The Owl and its night vision bring intuition, revelation, wisdom, and death, calling for transformation.

In turn, Celtic stories speak of the Wolf as a guide who walks closely with the god of the forest. The Wolf is also associated with freedom and the rediscovery of divine feminine power. The connection is not only with the mother Wolf who protects her cubs, but also with the Moon and feminine energy of the transformation cycles (see "The Red Cloak"). Its symbolism suggests the confrontation or integration between the "civilised" and tame version with the wild and instinctive aspects, represented by the She-Wolf, which is activated by the sharpening of the senses, the insight, the fierce sense of protection, but also the dedication, love, loyalty, and affection.

As for the highly intelligent Fox, she overcomes illusions, seeing clearly before moving on, showing humans how to overcome the fear of the unknown. Like all forest creatures, foxes have intimate knowledge of their environment and remain agile in their movement. The Celtic symbolism of this animal is reflected in an easy movement between dimensions.

Coif

The coif, the portion of foetal membrane — the amnion, or the placental membrane that surrounds the foetus and has its shape — with which some children are born, plays an important shamanic role, as it is what facilitates the journey between worlds. Carisa's son is born with the coif, which the elder woman interprets as an auspicious sign. In ancient languages, this word means "double skin" and "cap." Whoever is born with the coif is considered particularly powerful, and predestined, so to speak.

Its power manifests during sleep or trance, whether spontaneous or induced by dances or spells. The coif, situated on top of the head, remains subliminally important, for it is in this area that babies receive the ancestral sacrament of baptism.

Why are these tales important now?

INTRO, tale list and chapter references.

THE TALES

The Goat Girl - Belinda & Benilde & What breathes through the Tale

The Shepherdess - Hystera and the thread of life & What breathes through the Tale

The Red Cloak - Ananta the She-Wolf Woman & What breathes through the Tale

Lucífera and the Cauldron - The Cinder Girl & What breathes through the Tale

Carisa - The First Wailer & What breathes through the Tale

Monster Sanctuary - Brufe and the Bears & What breathes through the Tale

Queen of the West Sea - Oki-usa and the Black Rock & What breathes through the Tale

FOLLOWING CHAPTERS

Remembering the Tales / Disappointed Moors - The Disenchantment of Growing up Storyless, Part I

Disappointed Moors - The Disenchantment of Growing up Storyless, part II

Washing Moors - Washing History, part I

Washing Moors - Washing History, part II

Builder Mouras - Mythical Territory

Warrior Mouras - Guarding and Protecting the Sacred - Part I

Warrior Mouras - Guarding and Protecting the Sacred - Part 2

Enchanted Mouras - The Power of Imagination

Spinning Mouras - Telling and Weaving the Stories

From the Book - Contos da Serpente e da Lua, Sofia Batalha(in portuguese)

Nicholaj De Mattos Frisvold. “Serpent Songs”. “Mysteries of Beast, Blood and Bone

T.N.: In Iberia, the name “moro encantado” (Spanish) or “mouro encantado” (Portuguese) is a hybrid denomination for pre-agrarian chthonic spirits, sometimes confused with dryads, or goblins, as well as actual Moors who lived in the territory and professed the Islamic religion.

T.N.: In Greek, Θυσία [thysía] can be translated both as ‘sacrifice’ and ‘immolation’, indicating the deep association between fire and the smoke generated thereby.