Dear reader,

Please note that the content shared here on Substack will differ from what appears in the printed book. While many of the themes, stories, and inquiries may echo across both formats, the book itself has undergone a thorough process of review, editing, refinement, and expansion. In that sense, the printed version holds a more curated, deepened, and embodied iteration of the work.

Think of the Substack as a living ground, where ideas are still fermenting, evolving, and growing their tendrils. The book, meanwhile, is a vessel, harvested with care, ripened in its season, and offered as a more coherent ceremonial bundle.

With tenderness for the ongoingness of becoming,

—Sofia

The rescue and remembering of the ancient and complex systemic wisdom of the place we are and occupy has already taken us through some meanders, there being no end or beginning, for they are dendritic memories. It is, in fact, a lifelong process to be cared for and attended to with responsibility and integrity. To help us find these threads and cultural fragments, we now call the Warrior Mouras, the mythical beings who guard and protect places and their sacredness.

The Warrior Mouras may contain echoes of the Furies (and vice versa), called Erinyes, female chthonic deities of justice in ancient Greek mythology. The Furies were the three ancient Greek goddesses of vengeance and retribution who punished men for crimes against the natural order. They are three sisters considered older than any of the deities and their task is to hear the complaints lodged by mortals against insolence from young to old, from children to parents, from men to nature, and to punish such crimes by relentlessly pursuing the guilty. The Erinyes are old females and, depending on the authors, are described as having snakes in their hair, dog heads, coal-black bodies, bat wings, or bloodshot eyes. The Furies are associated with night and darkness, with varying accounts claiming them to be the daughters of Nyx, the goddess of night, or Gaia, the earth goddess. They live in the underworld and rise to the surface to pursue those causing various offenses. Being chthonic deities, they are often identified with pre-agrarian spirits, guardians of the fertility of the earth and their sentences and punishments are aimed at those who stray from their honour, respect or responsibility, as they protect the sacred truth of the regeneration of life. The Iberian Warrior Mouras reverberate in this same energy of fierce protection of what is sacred to them, helping us rediscover hidden and forgotten landscapes.

We celebrate their presence reclaiming the strength of ancient beliefs and worldviews in some of the principles that rooted the making of the Tales of the Serpent and the Moon.

Shamanism and the Sacredness of Nature

To understand the underlying structure of the tales, we have to consider the shamanic perspective.

Ancient (and current) animist and shamanic practices — terms that here refer to the integrated, systemic and sacred awareness and perception of living places — relate to a deep, primal and experiential direct connection with landscapes. The essential characteristic of shamanism speaks of the direct and personal visionary and mystical experience of the sacred or otherworldly through a journey outside the body, usually interpreted as a symbolic death and rebirth and often induced by psychoactive sacraments or through techniques of ecstasy. In the progression of Christianisation, many pagan or shamanic elements were considered heretical and were intensely and violently eliminated and forgotten over hundreds of years. The shaman, as a traveller of the sacred, is a practitioner of ancient techniques of ecstasy, something common in ancient accounts.

Despite persecutions and silencing throughout history, we continue in the presence of the figure of the European shaman through traditional tales, folklore legends, mythology and in later spiritual movements such as in hagiographies, the stories of saints that have so often adapted and incorporated older accounts and beliefs.

The term 'shaman' comes from the Tungus language of Siberia, and the word's origin relates to "animated, moved, created" and "knowing." Extasis, ecstasy, on the other hand, literally means "out of state" or alternative state of consciousness, promoting entry into a trance and a journey into non-material existences, interacting with spirits on behalf of the community. The shaman is a psychopomp — responsible for accompanying recently departed Souls to the afterlife —, priest, mystic and poet, and has a profound responsibility towards the human and more than human community, encompassing the entire surrounding ecosystem, not as a leader, but as a guardian of the regeneration of the multidimensional web of life. The shaman is the intermediary between the sacred and the profane, with unique features of each distinct culture unique in the space and time to which they belong. The union and personal dialogue with the sacred come from methods born of the specificity of the culture itself, always local and temporally contextualized.

The first references by the Greeks to the Keltoi, Celtic tribes who used ecstatic and visionary shamanic practices, in Central Europe and in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula date from the 6th to 4th centuries BC. These Celtic tribes, which some researchers claim originated in the Iberian Peninsula, emerging from the Iberian refuge of the last glaciation (Frazão and Morais, see bibliography), link them to the concept of the ancient bards and druids, the priests of the wisdom of oak and holly. Pliny, Roman writer, historian and official, gave the origin “dru” as derived from the Greek Drus, meaning oak (having the same meaning in Indo-European, the same root that gives the English word “truth”). The second element is connected to the root that gives rise to the English word “witness,” and relates to the knowledge of things personally and directly experienced. Thus, the meaning of druid is one who possesses enduring knowledge experienced personally. Both words, “druid” and “saman” (shaman), relate directly to wisdom, direct and experiential. In this form of shamanic and wilderness consciousness, there is no good or bad, or ideal; needs are enveloped by the contextual richness that generates them.

The rituals and practices relating to the sacred consider the specific nature of the place and time and not dogmas or pre-made recipes. It is multiple wisdom, contextual, direct and in flux, not mediated by institutions or external agents.

In turn, Tacitus, a Roman historian and politician considered one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars, expresses that the tribal Celtic gods are worshipped in the open air not being anthropomorphised, which underlines the animistic cosmology, where the sacred is everywhere and there is no need to build temples. Tacitus also refers to the fact that these tutelary spirits and divinities residing in specific places can only be seen with "the eye of reverence," that is, the direct perception of the divinity by contemplative means, that is, by ecstatic, trance or visionary shamanic practices.

We have found shamanism buried not far below the surface of our modern culture, for some researchers (see bibliography) think that the philosophers derived their peculiar ideas from entheogen-induced visionary experiences in shamanic rituals.

Sacred Plants

One of the fundamental presuppositions of this book is the fascinating "time when animals spoke,” the enchanted opening used in the tales, pointing directly to more than human dialogues that take place in altered perceptions of consciousness, whether shamanic, animistic or ecstatic. According to this argument, the legends, sagas and tales hold, between the lines, echoes and reverberations of recipes and precepts of primordial and archaic rituals.

Traces and remnants of ancient shamanic practices, old animistic customs, primitive totemic cults and ceremonies of initiation, fertility, birth, regeneration or death, are all part of the nuclear structure of some tales as we have been detecting. This "ecstatic knowledge" is directly related to visionary experiences and sacred pilgrimages to other dimensions.

In his 1992 book, “Food of the Gods”, author Terence McKenna, a north american explorer and scientist who spent part of his life studying the ontological bases of shamanism and the ethnopharmacology of spiritual development, states that: “The suppression of the natural human fascination with altered states of consciousness and the present perilous situation of all life on earth are intimately and causally connected. When we suppress access to shamanic ecstasy, we close off the refreshing waters of emotion that flow from having a deeply bonded, almost symbiotic relationship to the earth.” The author continues, recalling the antiquity of this relationship: “The first encounters between hominids and psilocybin-containing mushrooms may have predated the domestication of cattle in Africa by a million years or more. And during this million-year period, the mushrooms were not only gathered and eaten but probably also achieved the status of a cult.”

On the other hand, Jeremy Narby, a PhD in Anthropology by Stanford University and the author of the book “Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origin of Knowledge”, registers his initial scepticism when studying the ecology of an indigenous people in the Peruvian Amazon, where the local cultures, whose botanical knowledge astounds scientists, explain to him their knowledge comes from the hallucinations induced by certain plants. The author engages in a multidisciplinary investigation over ten years, from the Amazonian rainforest to European libraries, finding evidence that a consciousness primed by drugs can, in fact, receive accurate knowledge.

The ancestral hallucinatory, ecstatic or visionary experience is a cross-cultural phenomenon influenced by the biochemical effects of psychoactive drugs on the brain. There is archaeological and anthropological evidence that supports the thesis that mythical, mystical and symbolic episodes, distant in time and space, can correspond to the same experience, with different textures and expressions shaped by cultural differences, omitting and modifying elements according to the society and culture which experiences it.

On the other hand, as referred by several authors of “The Hidden World: Survival of Pagan Shamanic Themes in European Fairytales”, Indo-European-derived languages may not be mutually intelligible, but they nonetheless preserve rooted the idea that sacred visionary communion through botanical means, entheogens or sacred and magical plants and fungi, is one of the bases of direct knowledge and wisdom. In ancient European sacred traditions practising visionary shamanism, the verbal root for "seeing" is also the root for "knowing." For the Keltoi, or Celtic tribes, an "idea" is something archetypal, and the "theory" is a journey of going somewhere to have a vision, such as the mystical shamanic journey, based on the belief that this world coexists with another dimension, an underground and hidden world full of entities and possibilities, as well as interstitial layers of reality.

According to recent studies, mystical ecstasy is an individual experience that blurs the limits of the ego, bringing about a harmony with nature, where the ego is no longer confined to the body but extends outwards to all nature, and this total communion with the environment is felt as sacred, an authentic spiritual symbiosis, with each society and culture interpreting the experience in terms of its own beliefs and values. It is in the paradox between the healing potion and the toxic poison, between the sublime and the infernal, that we find the contradiction of magical plants, both in their capacity to transport the initiate into a state of rapture and retrieval of valuable sacred wisdom, and in the equally horrifying possibility of plunging into the caverns of the near-death experience, into truly grotesque worlds. Remembering the duality of the enchanting space, locus amœnus, where they encounter fairies, or the place of fear and horror, locus terribilis, where they encounter monstrous creatures.

States of trance stimulated by sacred plants can also be related to the ancient incubation rituals of descent into underground chambers inducing ecstatic sleep, trance, or little-death, rendering us absent from the ordinary world for long periods. The same state can also be provided by cadenced drum rhythms, harmonic choirs or ecstatic dances.

The ancients thought that during sleep, the Soul has a second life in a parallel universe. The Greeks spoke of the infernal darkness as a synonym for the underworld, and the experiences of sleep and death were considered identical. The dream state is a common theme in fairy tales, where the oniric rapture transports the dreamer into a distinctly separate temporal and spatial dimension, a parallel universe, as a temporal consciousness apart from the ordinary, often inhabited by fairies or mythical beings. Dreaming, or the visionary and mystical ecstasy, is a state similar to death, because figuratively the body, while asleep, presents an immobility and absence of consciousness like death. We find remnants of these rites in the metamorphosis metaphors of various tales, such as Cinderella or Sleeping Beauty.

The shamans claim to have experienced, since time immemorial, a communion with the fundamental chthonic-cosmic structures through the animated spirit of magical plants. In fact, more than ten thousand years ago there was already specialised knowledge about plants involved in funerary rituals and which were possibly used as mediation and communication with other worlds and dimensions. These sacred plants were one of the origins of the knowledge and feeling of the numinous, which expresses power and presence shared with a divine entity. Sacred botanical knowledge was one of the probable origins of visionary, mystical and sacred experiences, providing more than human communion and dialogue, mediating a direct relationship with the divine. As Carl A. P. Ruck states, these plants can in no way be called drugs, suggesting the neologism: sacramental entheogen.

The word entheogen literally means “inner manifestation of the divine,” and derives from a Greek word from the same root as “enthusiasm”, referring to religious communion under the effect of visionary substances, attacks of prophecy and erotic passion. This term was proposed as an elegant way of naming these substances without pejoratively judging sacred customs of ancient or indigenous cultures.

Entheogens of the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula is a territory of great indigenous antiquity. Just look for the huge legacy of megaliths, or even all the earlier finds. On the Portuguese side of the Algarves, the place “Porto dos Deuses Corvos” [EN: Port of the Crow Gods], sacred before Roman times. Throughout this Iberian territory the places have been repeatedly re-established, reflecting the layers and religion of the most recent dominant group, always with reinterpretation and rearrangement of the original symbolism.

With climate change and other environmental and human changes, such as the desertification of the Iberian Peninsula, once entirely forested with thousand-year-old trees, and the relocation of populations, the identity and knowledge of the archaic entheogens formally used in rituals have been forgotten, while new ceremonies have emerged over time, recreated in new rituals and shared in cultural fertilisations and exchanges.

As the authors of “The Hidden World: Survival of Pagan Shamanic Themes in European Fairytales” state, since the remotest ancient times, traces of sacred rituals using magical plants have appeared in the Iberian Peninsula. The use of plants such as the Devil's-fig tree (Datura Stramonium) and other solanaceous plants, mushrooms (Amanita Muscaria, the mushroom par excellence of fairy tales, and others), cannabis and also the sacramental use of the opium poppy are well documented. Solanaceae are implicated in many shamanic metamorphoses and journeys, with the characteristic induced psychosis causing the intoxicated person to imagine having become an animal, and the sensation of growing feathers and hair completes the hallucination.

Drinking potions, ritual foods, salves and ointments had solanaceous plants as main ingredients: datura used for flying, belladonna, meimendron or mandrake. Belladonna berries have been used since the upper Palaeolithic by hunters for a vision of success in hunting and during the chase to increase their senses and understanding, gaining stamina and sharpening ferocity. On the other hand, it is an ancestral custom that only women collect mandrakes, with respect and deference, in a ritual at dawn, and must penetrate deep into the forest until they do not hear the slightest sound of civilisation, lest the mandrake lose its magical potency. The art of sacrifice in Greek literally relates to "making smoke" — producing vision, inducing clouds of smoke, possibly with hemp sacrament or black tobacco —, being the origin of the word 'funeral' in Portuguese, and representing moments of frontier, impermanence and transition, guarded by ancestral rituals.

In rock art from the Iberian Peninsula, dating from the late Paleolithic, ten thousand years ago, a shaman is depicted climbing the cosmic tree, like the bear, to steal honey from the bee, with a leather bag to store it, recalling the phenomenon of intoxicating honey, bringing back the memory of the honeycomb as a metaphor of sacramental food as well as a trans-global archetype. This is one of the earliest pieces of evidence of the relationship between man and honey and is found in cave paintings in a cave in Valencia, Spain.

In these deep-time traditions, animals are the main actors, full of totemic and mythical connections, because the animal, by eating the magic trance-inducing entheogen, shows the shaman the way to become of the same substance as the divine power, crossing dimensions and retrieving valuable contextual wisdom. Many animals are attracted to mushrooms or psychoactive plants, such as the horse, the deer, the wolf or the raven. They are guardian creatures of sacred plant knowledge full of herbal symbolism and antiquity, as are snakes with their venom, bears with their magical hibernation, bees as Souls and messengers of the gods, boars and goats that eat everything and guard the paths and portals. These are just some animals that speak, guide or transform themselves in the living tales.

Why are these tales important now?

INTRO, tale list and chapter references.

THE TALES

The Goat Girl - Belinda & Benilde & What breathes through the Tale

The Shepherdess - Hystera and the thread of life & What breathes through the Tale

The Red Cloak - Ananta the She-Wolf Woman & What breathes through the Tale

Lucífera and the Cauldron - The Cinder Girl & What breathes through the Tale

Carisa - The First Wailer & What breathes through the Tale

Monster Sanctuary - Brufe and the Bears & What breathes through the Tale

Queen of the West Sea - Oki-usa and the Black Rock & What breathes through the Tale

FOLLOWING CHAPTERS

Remembering the Tales / Disappointed Moors - The Disenchantment of Growing up Storyless, Part I

Disappointed Moors - The Disenchantment of Growing up Storyless, part II

Washing Moors - Washing History, part I

Washing Moors - Washing History, part II

Builder Mouras - Mythical Territory

Warrior Mouras - Guarding and Protecting the Sacred - Part I

Warrior Mouras - Guarding and Protecting the Sacred - Part 2

Enchanted Mouras - The Power of Imagination

Spinning Mouras - Telling and Weaving the Stories

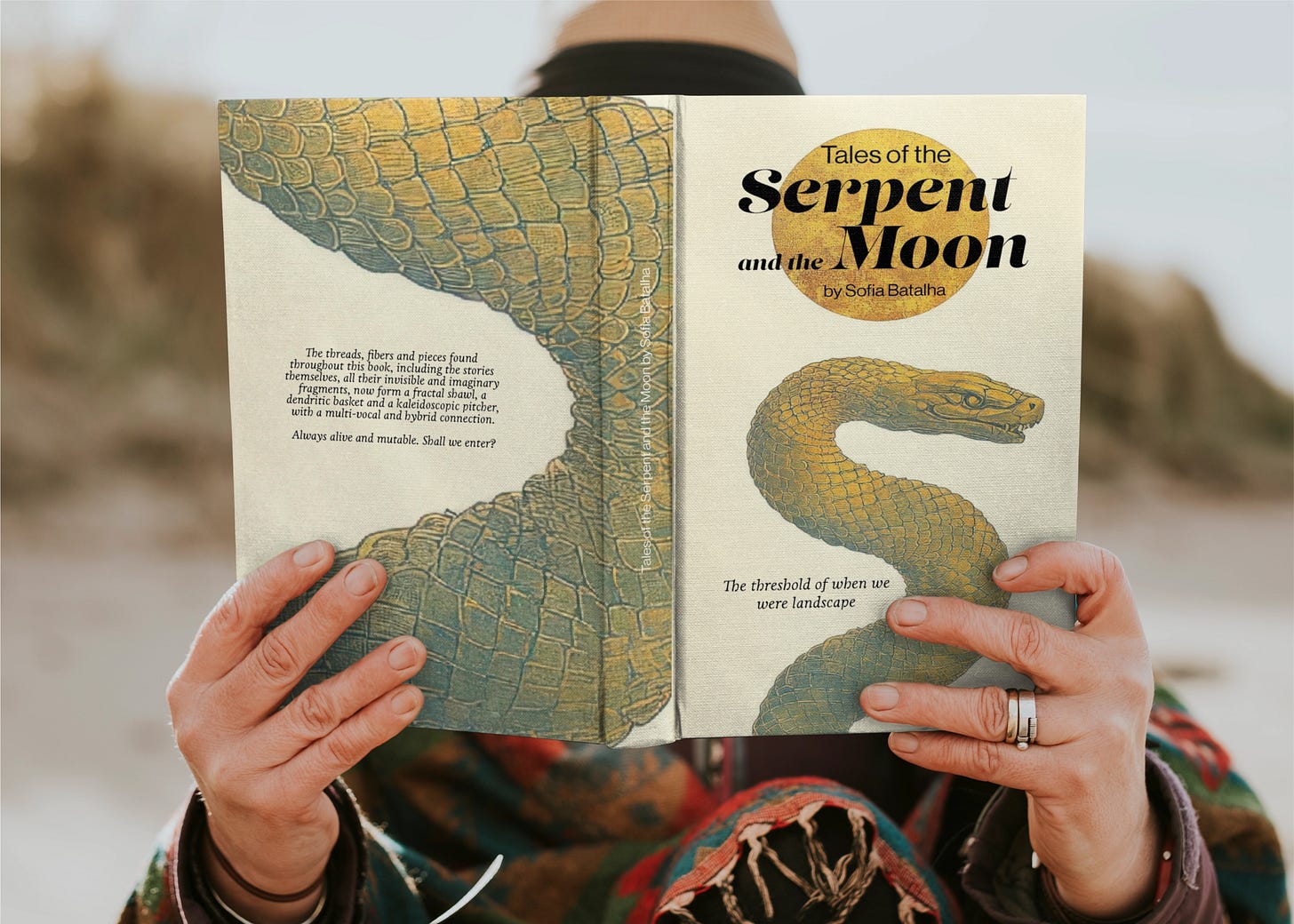

From the Book - Contos da Serpente e da Lua, Sofia Batalha(in portuguese)