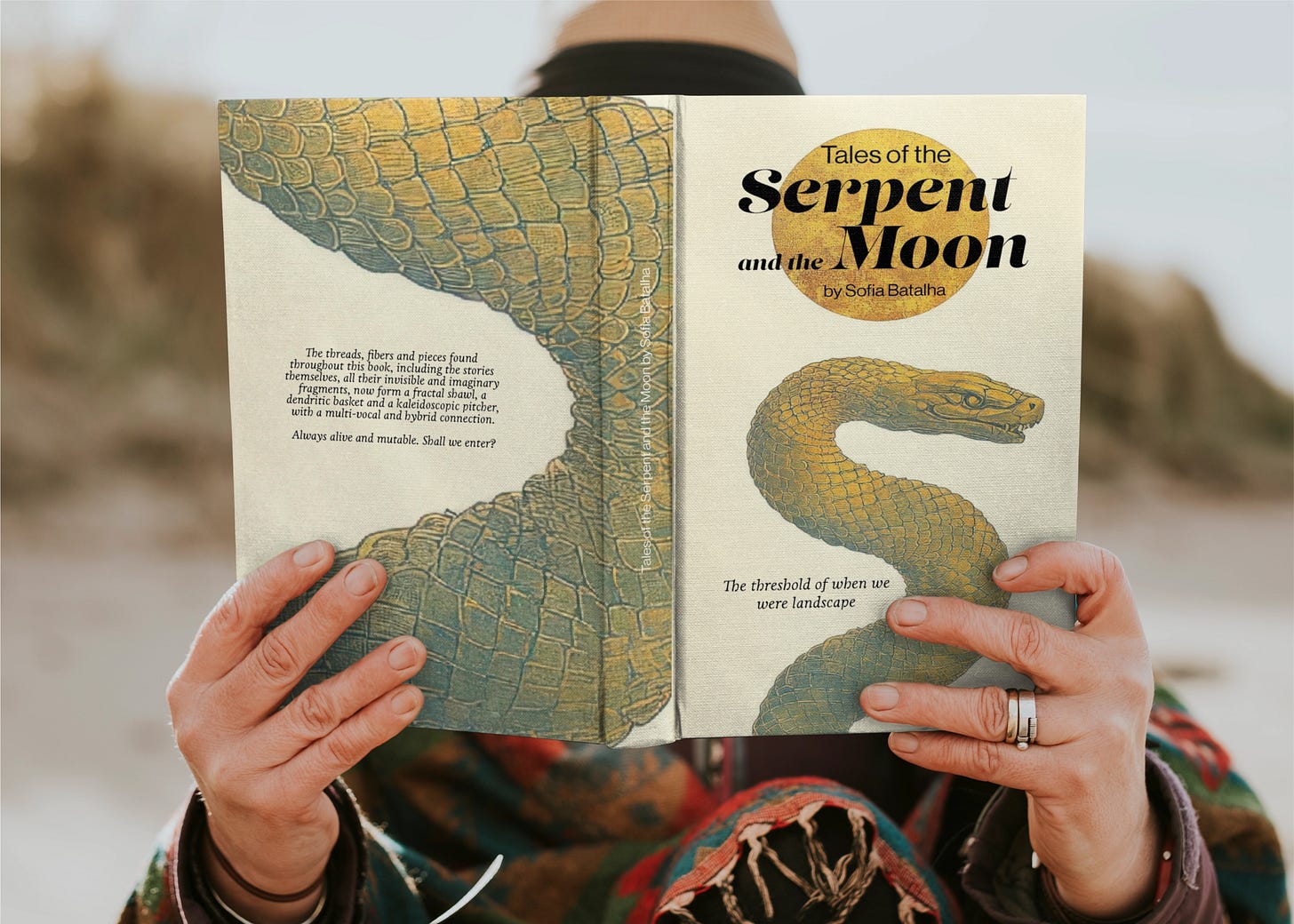

Dear reader,

Please note that the content shared here on Substack will differ from what appears in the printed book. While many of the themes, stories, and inquiries may echo across both formats, the book itself has undergone a thorough process of review, editing, refinement, and expansion. In that sense, the printed version holds a more curated, deepened, and embodied iteration of the work.

Think of the Substack as a living ground, where ideas are still fermenting, evolving, and growing their tendrils. The book, meanwhile, is a vessel, harvested with care, ripened in its season, and offered as a more coherent ceremonial bundle.

With tenderness for the ongoingness of becoming,

—Sofia

The Story

In ancient times, in a castle of black and pearly granite, there lived a court with a kind King and Queen. They took care of their kingdom, were just and kind to their subjects, and so very popular and cherished among them. They took care of the families who planted the grain and fruit, and the ones who cared for the animals and the land. Furthermore, they distributed the harvests, and no one was left without food.

They organised sumptuous feasts and banquets, with jugglers, dancers, and bards who enlivened the darkest nights. The castle's stones, still alive, resonated with poetry and music.

But despite this, a deep sadness also dwelled inside them, and they often wept. They were unable to have children, and the Queen was miserable. In the dark of night, she howled in pain. One full moon night, touching her empty belly, she remembered a story her grandmother used to tell her—a story that might have the solution to all her troubles.

She gets up suddenly, and looks over at the king, sleeping peacefully. She then directs her gaze to a large, old oak chest at the foot of the bed. The soft fire from the fireplace warms her back in a comfortable embrace and makes the chest almost glimmer in its light. She opens it as quietly as possible and rummages through it, finally finding an old shawl, beautifully woven with an intricate shape-shifting pattern of living spirals. Her grandmother had whispered that the Shawl had Magic, ancient Magic, and would bring help to those who had it in times of trouble, but it should also never be worn without accountability.

The shawl, carefully kept in the ancient wooden chest, had been in the family since time immemorial, passed down from mother to daughter. Each woman in the family touched it with care and attention, wove and mended it, from those whose names had already been forgotten to the present generations. Its origin was lost in the mists of time. But grandmother would tell, on cold nights by the fire, that it was originally woven by an ancestor who lived on the edge of the forest, a wise woman who wove the wisdom of stones and memories. The Magic Shawl woke the ancient guardians of the place, for it played their melodies. At that very moment, thrust forward by the flood of memories, the queen fled out of the castle and through the moonlit fields. She knew exactly what she had to do.

On and on she ran, through the forest, stumbling, but in trust. Suddenly, she came to a halt, gasping for breath, and gripping the Shawl tightly around her shoulders. In front of her, in the heart of forest, stood an ancient stone, brightly lit by the milky moon in the clear night sky above.

She reassured herself—you know what to do. She knew she had to pass the old shawl over the ancient stone in the forest centre and wait. Dropping the shawl on top of the rock, the exhausted Queen fell to her knees on the ground and became, at once, fully aware of where she was, completely alone and barefoot.

For fear she wept, for anger she howled, for loss and an empty womb she lamented. She lost track of how long she had been waiting there. She fell asleep, and when she woke up, she saw, out of the corner of her eye, a gigantic black snake crawling out from under the sacred stone. Frightened by the sight, she scrambled to her feet to run away, but she bumped into a very old woman, bent over and hunched up, who just seemed to have always been there. The old woman of the rock tells her: "To break your spell, you must come to the crag on the next full moon, and cry. Your lament must be visceral, leaving no tear unwept, releasing all your pain to the womb of the earth and the fresh water that flows through it. If you do so, the next morning, you will find two figs, one dried and the other ripe. You must only eat the ripe fig, and under no circumstances should you eat the dried fig."

The Stone’s elder continues to murmur warnings, but the Queen is no longer listening, for, her anxious heart is already set on the next full moon. Her eyes closed tight, her face turned upwards to the night sky, one hand clutching her belly, she allows her full weight to lean against the Stone before her body falters and she slides, gradually, down to a crouch, her back against the hard, smooth rock. The Elder continues in her ancient voice: "From the sixth year on, you'll need to take special care on the black moons, and by the twelfth year everything will cease."

The Queen wakes up in the morning on the forest floor near the hewn stone, and as she opens her eyes, she sees the tail of a snake nestling under the rough rock. In a leap, she takes the shawl and runs back to the castle. She arrives hours later, when the king has already sent men to look for her. He receives her with open arms and takes care of her tired and bloody feet.

A month later, the Queen does as the old woman of the Stone whispered to her. She shouts out all her pain into the crag throughout the night, drying the tears of her grief. Tired and exhausted, she eventually falls asleep. When she wakes up with the sun rising on the cold rock, she finds two figs, as the old woman said —one dried and one ripe. In a wild craving, she swallows the dried fig in one gulp. Something inside her reaches down and pulls. Strong, alive, and powerful. I shouldn't have eaten this fig; she thinks, disappointed in herself. But no one saw it. So, she sits down with the dignity of a queen and delicately eats the sweet, ripe fig that voluptuously still awaited her on the stone.

Back at the castle, on that very night, another lavish banquet is organised, and the Queen’s happy disposition shines through. The King finds her quite irresistible, and they fall asleep with sated abandon in each other’s arms.

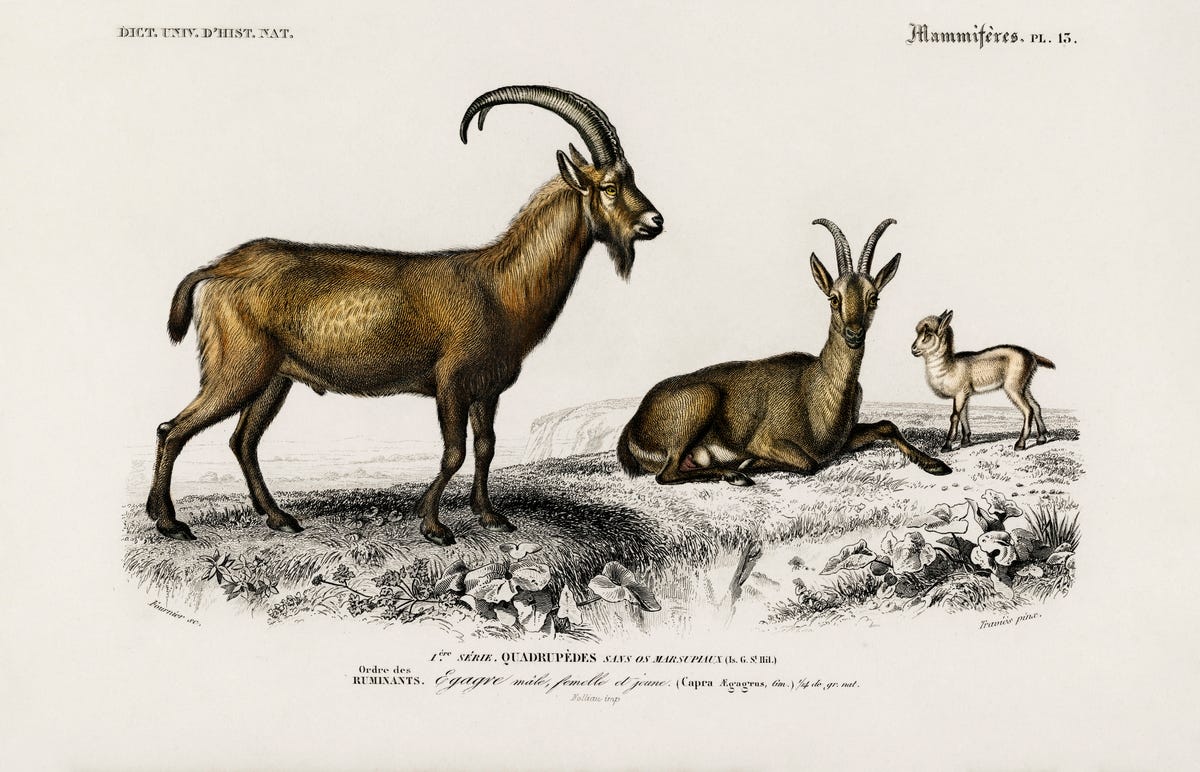

Ten moons later, after a resplendent and joyful pregnancy, the Queen goes into labour. Everyone in the castle is in a great bustle to assist the Queen in that sacred moment. The midwife is in the room with her, and tells the Queen it is time for the baby to be born. After three contractions, the Queen gives birth to a little goat. A little goat with wet and bloody hair, barely able to stand. Soon after, out comes a little girl, plump and perfect. At the King's request, the little goat, left unnamed, is discreetly left at the edge of the forest by the perplexed midwife, while the little girl—Belinda, they call her—, grows up in a cradle of gold in the castle, surrounded by nurture, affection, and attention, as well as poetry and music. She learns to weave, sew, mend, cook, write and sing. She grows up happy, but constantly longing for something she can neither express nor explain.

As for the little goat, left at the edge of the forest, while still not strong enough to stand up, she is gone the next day. "It must have been taken by wolves," thinks the King, with relief. Yes, she was taken, but by rough and scaly hands that support her in those first hours. Wise and warm hands that nurtured her. The little goat is given the name Benilde, and the name’s whispered among the stones.

Benilde, the little goat, grows in curiosity and freedom, embodying the wild wisdom of the forest, climbing the highest cliffs, drinking water from springs, eating figs and blackberries in summer, and finding cosiness in winter. But she, too, has wandered the woods for six years, searching for who knows what. Benilde knows these paths as well as her hooves, her fur vibrates with the storms, and her horns twitch with every discovery. She knows every nook and cranny, from the highest peaks to the deepest chasms, tastes every herb, and finds company in other animals. She grows agile and strong, but nevertheless, there’s always something missing. She wanders, always searching and probing, with an eternal longing for something she’s unable to grasp.

The year the sisters turn six, something strange happens on the night of the summer solstice: Benilde suddenly loses her woolly hair and horns and becomes a girl, while Belinda suddenly grows hooves and becomes a goat. The Goat Belinda, running free in the palace, creates chaos in the court under her father's anxious, worried gaze and her mother's confusion. She climbs onto tables, eats curtains, and discovers a new way of being in the world. The Girl Benilde, now with new soft hands and delicate skin, meets the old woman who had taken care of her in the forest, and is told that she is almost home. Without her fur, Benilde is cold and feels lost.

The next morning, both Girl and Goat awake to find they have returned to their old bodies. Everything is in its place once again. Benilde leaps through the forest, and Belinda mends her old shawl in the castle. However, from that day on, every black moon, the sisters transmute their bodies, switching places, and thus experiencing other places of being. Over time, remnants linger after the transformations: goat's feet and small horns in Belinda, or human ears in Benilde. Both are hybrids of girl and goat, of castle, cliff, and forest. During sleep is when the metamorphosis takes place, sometimes gentle, sometimes violent, and always painful. The body moves, changes, and transforms itself. The will is altered.

Belinda dreams more and more clearly of the forest, of her twin sister, and near her twelfth birthday, she knows what she has to do. She knows she has to leave the castle, leave for the Unknown, so she can finally return home.

The weeping Queen offers her the shawl as a birthday present and knows that she has to let Belinda go her own way. Heart in hand, the King and Queen let her go, not knowing if they will ever see her again, but those who love must set their beloved free. The apple of their eyes makes her way through the wild forest with the Magic Shawl on her shoulders. Strangely, Belinda knows those winding, dark paths. She could walk with her eyes closed. She follows slowly, savouring this oddly familiar place.

Her heart starts as she reaches the stone in the forest's centre. It beats hard against her chest. On the other side is a goat, looking wise and alive. They share a brief look and run to each other with a happiness never felt before. Both now at the age of twelve, they walk together to the edge of the crag, the same one where their mother wept, where her tears of salty lament were given over to the wild wisdom of the forest. As the sisters embrace, the serpent comes out of the rocks and coils around the goat-girls, squeezing them and bringing them closer together, closer, and closer still.

They merge, transmute. No longer alone, always together. They don't need to look, search or wander any further. Their psyches alchemize into one body, for the Soul had always been one and only one. The girl-goat who knows the deep mysteries of the forest and speaks the language of men. The goat-girl who knows the castle, all its stones, and never gets lost in the forest.

The Goat-Girl decided to lodge herself at the edge of the forest, between worlds; between the wild and winding paths and the straight roads. She became a woman, a bridge-woman, a medial guardian of all rocks, nooks and crannies. She kept her goat's feet, to remind herself of the path and her service. From the edge, she served, and for many years, mountains, men, and beasts alike, for she knew the ancient language of the earth.

At her death, she became stone. The Shawl continued its story in other skillful hands.

After the story, please take some time to feel how it relates to you and what unfolds and resonates with your unique context.

Let's breathe.

What breathes through the tale

What follows is not a symbolic interpretation of the tale, exiling it in a single narrative. There is a unique symbiotic dialogue with its living layers that is yours to feel, sense, and travel through. The following words are mythical, historical, and place transcontextual information that resonates with the tale pulsing realm.

This tale was dreamt whole, having been offered to me, and I just wrote it down. As it emerged so spontaneously, I then looked for references and echoes of where it might have come from.

Quite a few things emerged. The first is a reference to a story that has always fascinated me: the tale of the “Goat's Foot Lady”. In this Iberian folktale, the nobleman Diogo Lopes (or Diego Lopez from Bizkaia) was out hunting when he met a beautiful lady, with whom he immediately fell in love. He was surprised that she had a goat's foot, but he was so enchanted that he wanted to marry her anyway. She accepted, provided he promised never to bless himself again, creating a connection to archaic pagan religions. She eventually runs away, years later, for fear of retaliation for being seen as a demon by the populace. Not only that, but she takes their daughter, while the son stays with his father. Years later, the son, now a knight, appeals to his mother to help him save his father, who had been imprisoned by the Moors, which she does, thanks to a magical white steed, named Pardalo—remembering that, symbolically, horses are mythical psychopomps who know the way of transition between worlds, taking those who ride them on a pilgrimage of wisdom, rescue and deep metamorphosis. This tale of the Goat Girl is the origin story of the Goat's Foot Lady, of sorts.

There is also the Portuguese folktale called “Little White Lamb,” where a queen has a little lamb instead of a son, and he wishes to be married. He was a cursed prince who had to be married three times and undress seven skins, but his bride fails to lift the spell. He remains cursed for the next seven years, and the bride must look for him in the palaces of the Moon, the Wind, and the Sun. Eventually, she recognizes him, now in the form of a bird, and rescues him from the enchantment.

Another reference is the Scandinavian folklore tale, “The Lindworm,” where a "half-man, half-snake" tapeworm is born as one of the twins of a queen, who, to overcome her childless situation, follows the advice of an old woman, who tells her to eat two onions (or flowers, depending on the version). The queen did not peel the first onion, causing the first twin to be a gigantic worm, tapeworm, or snake. We should recall that onions, flowers, and figs have deep-time affinities with chthonic black goddesses. Ancient Cybele has connections with cebolas (the Portuguese word for onions), and the fig fruit is an inverted flower, connected to the mother’s milk and the vulva, as well as with, the roman goddess Fauna’s ritual purge ceremonies1. Demeter was also connected to the fig tree. In ancient Kemet, the fig tree was a portal to the goddess's underworld or sacred womb, marking places with underground water. The fig is connected with visionary wisdom, being associated with the fruit of knowledge by Hebrews and Canaanites (Phoenicians), through ancient shamanic ecstatic rituals. The powerful fig tree is an ancient axis-mundi. A Portuguese popular saying goes that “A fig tree always grows where someone falls,” the stumbling makes the ground rumble, and the fig tree emerges from the depths. The ancient power of the inverted flower. Wasp nest. Sweet mother earth milk. Slave revolution. Celebration. Primal mother embrace. Reverse matrix. Doing things differently. Nurture the tumble. Root deep and branchy communication.

There is also the Italian version of the girl who enters a sleeping trance, “The Sleeping Beauty,” where she is magically conceived by the actual ingestion of a rose petal, again echoing the archaic image of herbal and magical fertilisation. In a lesser-known version of Snow White, where they are actually two sisters, "Snow White and Rose Red" both are the same persona2, or more precisely, are dichotomous and reciprocal halves of the same thing, complementary opposites of winter and summer—white and cold vs. red and hot, in an ancient version of the codification of the solar seasons.

The Double

These two tales, "Snow White and Rose Red," and “The Lindworm”, take us into the dimension of reunification with the wild twin, one of the fundamental patterns of the Goat-Girl tale. The integration with the double, an immaterial or zoomorphic part of one's self which, under certain circumstances, can separate from the body and live its own life. It does not correspond to the Soul, but to another essence, like an image reflected in a mirror. This ancient concept is widespread throughout shamanic and pagan antiquity. This is such an ancient and powerful theme that, regarding the birth of twins, the Church thought that only one could have a Soul, for the other would be a demon child.

There is an archaic and complex mix of concepts and ideas reflected in the Shamanic belief of the "Soul of bones," a sacred part of the human being that resides in the bones, which enables the intimate relationship between the individual and his double, his complementary opposite of the spiritual mirror. In many shamanic cultures, the bones are thought to contain the living being's life force, and the double can be rescued if the bones remain intact. This double, like shamans or their animal relatives, can travel far, allowing them to have knowledge of and participate in acts that take place even at great distances in space and time. To contact him, the shaman enters an ecstatic trance, as if he were dreaming.

The double brings the image of integration between the domesticated and the wild, rescuing this essential and primordial relationship from exile. The goal is some form of reintegration, relationship, and dialogue.

According to legacies of mediaeval European literature, a person can dream prophetically of their double since, in the dream state, he can access his animal form. The metamorphosis from human to animal materialises in dreams and visions, as well as in reality, according to shamanic experiences. There is also the dimension of fairies and witches; they live in a parallel dimension, with full and often prophetic knowledge of their human counterparts.

The Goat

The Goat is an animal full of both symbolism and shamanic and herbal wisdom. Its well-known taste for ecstasy induced by sacred plants or mushrooms is part of its metaphorical complex, and it is often implicated in the discovery of psychoactive plants and subsequent revelation, due to its habit of grazing on everything.

Goats were part of living ecosystems, being focal seasonal animals, and helping early human communities to perceive cyclical land patterns.

The goat was among the first animals to be domesticated, so its presence and resonance with human communities will take place quite early, in a very ancient relationship. Their presence includes their body heat; the abundance of milk and its derivatives; or even their meat and skin.

Many cultures today are familiar with goats, domesticated or wild, as a very present figure in mythologies and folklore. In Europe, we have the pans, fauns, or satyrs, all hybrids of goat and man.

Goddesses and the Goat

The goddesses Ataegina (Iberian pre-agrarian goddess), Artemis, and Diana are all represented by wild goats. Goats are attuned to chthonic and telluric energies, able to move strategically through difficult topography and go where other animals cannot, surviving in harsh environments.

The Shawl

Finally, we have the reference to the shawl, which runs across all Tales of the Serpent and the Moon. Although the official history places the shawl in Portuguese territory in the 19th century, its local forms and presences are much older, for in the countryside, women have always worn coats on their backs, be it a folded skirt, a cape, capucha [hooded cape] or mantéu [mantle].

The shawl appears in this tale as the Queen's feminine legacy, the ancient Magic Shawl, which should never be worn recklessly. Here the Shawl is a talisman, an enchanted amulet of more than human dialogue, a weave of connection that redeems sensitivity and whole presence. This talisman possesses magic, being deeply connected to rituals, unravelling and finishing, woven by ancient guardian hands, those that care and nurture, reminding us that we receive not only intergenerational trauma but also much love, nurture, and presence.

The pattern woven into this shawl is mended and recreated by living rhythms, pulses, and melodies. It is a primal chant of embodying the earth and the cosmos, being and weaving life. Its presence is sacred.

This ritual piece represents the power of orality embedded in a living thread, woven and mended by the heart. Fibres are woven in reverence and breathed with life, interwoven between the threads and one's own body, hands, and voice.

The shawl passes the valuable legacy of feminine powers and mysteries from generation to generation, and echoes entire lives in all their transitions. It serves to protect and to cherish, as it can cover, envelop, or conceal, and, traditionally, it is the piece passed down from mother to daughter since there is not much else to inherit.

Its use can be either daily or magical and ritual, on the body, in the house, or in the territory. It has symbolic links to cloaks, veils, and capes, and can be worn in reverence, raising levels of perception. Its use extends from the beginning of life—wrapping and warming the newborn, paying the midwife—, to the end of life—wrapping the deceased or the pain of mourning, preparing for burial, as well as serving demonstrations of power, or hiding poverty.

The web or plot of the shawl in this story(ies) is to open doors to the nurture of life’s generating mystery.

Why are these tales important now?

INTRO, tale list and chapter references.

THE TALES

The Goat Girl - Belinda & Benilde & What breathes through the Tale

The Shepherdess - Hystera and the thread of life & What breathes through the Tale

The Red Cloak - Ananta the She-Wolf Woman & What breathes through the Tale

Lucífera and the Cauldron - The Cinder Girl & What breathes through the Tale

Carisa - The First Wailer & What breathes through the Tale

Monster Sanctuary - Brufe and the Bears & What breathes through the Tale

Queen of the West Sea - Oki-usa and the Black Rock & What breathes through the Tale

FOLLOWING CHAPTERS

Remembering the Tales / Disappointed Moors - The Disenchantment of Growing up Storyless, Part I

Disappointed Moors - The Disenchantment of Growing up Storyless, part II

Washing Moors - Washing History, part I

Washing Moors - Washing History, part II

Builder Mouras - Mythical Territory

Warrior Mouras - Guarding and Protecting the Sacred - Part I

Warrior Mouras - Guarding and Protecting the Sacred - Part 2

Enchanted Mouras - The Power of Imagination

Spinning Mouras - Telling and Weaving the Stories

From the Book - Contos da Serpente e da Lua, Sofia Batalha(in portuguese)

“Fauna, Ancient Roman Goddess of the Wild Places and Animals.” Thalia Took, http://www.thaliatook.com/OGOD/fauna.php.

A.P. Ruck, Carl, et al. The Hidden World: Survival of Pagan Shamanic Themes in European Fairytales. Carolina Academic Press, 2007.